Arctic tourism in the age of Instagram

When most people think of Arctic economic development, things like resource extraction are usually first to mind. But northern regions and chambers of commerce are increasingly touting tourism as a key economic tool.

It’s seen as an industry that creates jobs for a variety of education levels, promotes small-scale entrepreneurship, reinforces and promotes local cultures, and creates the sustainable development lacking in many of the expensive and hard-to-get-to regions of the North; whether the remote Indigenous communities of Arctic Canada and Greenland, or the villages of Finnish Lapland and northern Russia.

But tourism is far from the benign industry it’s often made out to be.

As Iceland has discovered, mass tourism in the North can have social and environmental impacts as profound as those of the mining or drilling industries.

Yet successive governments did nothing to prepare for any of it. Instead, Instagram and Justin Bieber inadvertently ended up doing most of Iceland’s tourism planning for them.

Now, not everyone is sure they’re happy with the results.

To find out more, Eye on the Arctic’s Eilís Quinn travelled all over Iceland: along the country’s famed Golden Circle tourist route near Reykjavik, to remote farming settlements in the southwest, and to the dying fishing villages of the Arctic; to find out who tourism is helping, who it’s hurting and what other circumpolar regions can learn from the Iceland experience.

Journalist: Eilís Quinn

Web Editor: Jean-François Villeneuve

The social & environmental impacts

GOLDEN CIRCLE, Iceland — Whichever way you look at it, Iceland has a lot to thank tourism for.

It’s bringing in over two-million visitors a year, contributing almost 800 billion ISK ($10 billion CDN) to the total annual GDP and, oh yeah, almost single-handedly saved the country from the 2008 economic collapse, the worst financial crisis in modern memory.

But ask the average Icelander how other circumpolar regions might replicate their country’s stunning tourism success, and the answer may surprise you.

“In one word?, Don’t.” says Einar Torfi Finnsson, director of the Reykjavik-based Icelandic Mountain Guides. “Learn from our errors instead.”

(Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

“What’s going on is not sustainable”

Finnsson is among an increasing vocal cohort of Icelanders sounding the alarm on the country’s explosive tourism growth, even when they work in the industry themselves.

“Being Arctic and sub-Arctic like we are, our whole environment is fragile.” Finnsson says. “Between 80 and 90 per cent of visitors say they come to Iceland for the nature, but we’re flooding these natural sites with tourists without protecting it. If we spoil all our interesting nature by trampling it down, we destroy not only the reason people come to Iceland, but the ability of people to enjoy it when they are here.”

“Tourism saved us from the depression after the bank collapse. It put bread and butter on the table for a lot of people here, so it’s dangerous to talk tourism down directly, but we have to start addressing this.”

“What’s going on is not sustainable.”

When tourism goes boom

The cultures, histories and geographies of the world’s northernmost regions vary wildly. But the stunning growth of Iceland’s tourism industry has triggered the imagination of Arctic and sub-Arctic regions ranging from Canada and Greenland to Finland and Russia.

(Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

When most people think of Arctic economic development, the first things that come to mind are resource extraction and exploitation. But on the ground, tourism is increasingly being touted as an important economic tool by northern communities and chambers of commerce.

Unlike things such as resource extraction, tourism is seen as an industry that creates jobs for a variety of education levels, reinforces and promotes local cultures and creates the sustainable development lacking in many of the remote, expensive and hard-to-get-to regions of the North.

In Iceland’s case, the numbers are staggering.

Less than 10 years ago tourism trailed behind Iceland’s fishing and aluminium industries. But now it’s overtaken all combined to become the main driver of the economy.

In 2017 alone, more than two-million visitors made their way to this country, more than six times the Icelandic population of only 348,000 people .

It could all have been an economic fairy tale, except for one thing.

No matter the parties in power, no one in successive governments prepared for any of it.

Instead, Instagram and Justin Bieber inadvertently ended up doing most of Iceland’s tourism planning for them.

“You may not like the results you end up with.”

Most Icelanders put the country’s tourism success down to a confluence of one-off events that would be almost impossible for other circumpolar countries to replicate even if they wanted to: the 2008 collapse of the krona, the eruption of the Eyjafjallajokull volcano in 2010 that reminded the world that Iceland, well, even existed, and the subsequent deluge of budget flights making the country a quick and cheap plane ride away from most European and North American capitals.

And then came Instagram.

(Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

(Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

“It’s insane actually.” says Finnsson. “I could never have imaged the effect of social media. People come and want to check the box for the most popular Instagram- and Facebook- driven natural sights. And it’s not about getting a particular picture anymore, it’s about getting the picture at the exact same place, and exact same angle, as they saw on social media, even if you tell them there’s something better or more beautiful somewhere else.”

The problem is, little was done to educate tourists about the fragility of Iceland’s nature, once they got here.

And by the time decision-makers realized this might be problem, millions of pairs of feet had already trampled away swaths of fragile sub-Arctic vegetation at the country’s major sites.

(Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

“It was a total lack of planning.” says Rannveig Olafsdottir, a tourism studies professor at the University of Iceland in Reykjavik.

“You as a nation must decide what areas should be developed and for which kinds of tourism. Because if you don’t, then the hundreds of thousands of tourists will decide for you, and you may not like the results you end up with.”

Guiding, education and get off the d#mned moss!

Harald Schaller is a former park ranger, and now a project manager, at Thingvellir National Park, and experiences the challenges of educating the public first hand.

It should be a dream job.

Home to Iceland’s first parliament in 930AD, Thingvellir is a UNESCO world heritage site and straddles spectacular landscape with a giant fissure (Almannagjá) that marks the division between the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates.

But on the afternoon Eye on the Arctic visited, Schaller was simultaneously answering visitor questions, preparing to welcome a school group, then periodically jumping up to run after tourists who’d walked past warning signs, ropes, and even barricaded paths, to trample the vegetation for a better picture.

If trampled, it can take 30 to 40 years to grow back.

(Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

“They make our job very difficult.” said Schaller, also a graduate from the University of Iceland’s Department of Geography and Tourism where he researched sustainable travel. “I don’t blame them but I care about this land so I feel a little sad and angry sometimes.”

As a volcanic island in the sub-Arctic with a harsh climate and very little topsoil, Iceland’s moss takes 100 to 200 years to develop. Growing only a millimetre a year, if the vegetation is severely trampled, it can take some moss species 30-40 years to regain their strength and composition.

“Everyone thinks they’re the only one stepping off the path to get that particular picture.”, Schaller said. “They don’t realize there’s now hundreds of thousands of visitors before and after them thinking the same thing.”

“And then you have Justin Bieber.” Schaller says, referring to the infamous 2015 I’ll show you video, now with over 405 million views on YouTube, where the Canadian singer rolls through the Icelandic moss, swims in glacier water and conducts other activities described by locals as everything one actually should not do while in the country.

“We work very hard to educate our visitors.” Schaller says, “But in the end there’s only so much we can do.”

The social impacts

But the environment isn’t the only thing in Iceland under pressure.

Successive governments have also failed at restructuring the country’s micro-bureaucracy, set up to serve 300,000-odd Icelanders, to keep up with the demands millions of tourists are placing on everything from the health care system to law enforcement.

The South Iceland District Police division is responsible for most of the southern part of the country, which includes the famed Golden Circle tourist route.

In 2017, approximately 1.9 million tourists visited this region.

Yet police staffing levels haven’t changed from 2006 and there are still only ten officers on duty a day to respond to whatever happens in their 31,000 sq km territory, a region which includes everything from the arctic highlands to the sub-arctic lowlands.

“It’s absolutely crazy and we are suffering a lot.” says Sveinn Kristjan Runarsson, the chief superintendent of the South Iceland District Police. “I feel the difference in my officers. I see they are getting tired and pushed to the limit. It’s not just the hours and overtime, but seeing the fatal accidents and serious injuries.”

A major problem is tourists driving off-road in rented cars and being unfamiliar with Iceland’s narrow roads, harsh weather and nature.

“They’ve never driven in snow or on ice before, they’ve never driven on gravel roads before. They get stuck in the mountains, in rivers, everywhere. It’s very challenging.”

(Eilis Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

(Eilis Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

Also leading to death and injury are tourists ignoring signs warning of super winds near cliff edges or dangerous tides.

Several tourists have died at natural sites around the country.

Reynisfjara, a beach near the village of Vik is notorious for the so called ‘sneaky wave’, a vicious breaker that pulls the stoney black sand out from underneath your feet.

“It whips you around like a washing machine and once it’s pulled you in you can’t get out of it.” Runarsson said. “Locals know to stay away, but visitors are looking through their cameras and not aware of their surroundings.”

(Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

What now?

Iceland’s current coalition government, led by Prime Minister Katrin Jakobsdottir and in power since November 2017, has sent signals it plans to tackle some of the country’s tourism challenges during their mandate. These include the adoption of a three-year plan initiated by the previous government to make more funding available for natural site planning; the possible imposition of airport fees that could help fund tourism infrastructure; and whether commercial tourism operators should be licensed before they’re allowed in national parks.

Thordis Kolbrun Reykfjord Gylfadottir, Iceland’s minister of tourism, industry and innovation, didn’t respond to repeated interview requests by phone and email over a two-week period to comment for this piece.

The Ministry of Tourism, Industry and Innovation said Gylfadottir was not available for comment and that no one else at the ministry was available to discuss the current government’s tourism strategy or vision.

Tour guide Einar Torfi Finnsson describes some of the new government’s ideas as “promising”, but that what the country really needs is a comprehensive tourism strategy that encompasses everything from environment and economy, to public services and industry.

“Unfortunately, I’m not too optimistic.” Finnsson says. “It’s not in Icelandic culture to be proactive. Sometimes I wonder if all this has gotten so big, so fast, it’s already too late.”

Iceland’s rural revival?

HOFSNES FARM, Iceland — An elementary school with only eleven students could mean many things for a place.

Community survival would not usually be one of them.

But in this remote farming settlement in southeast Iceland, eleven is reason to cheer; because after years of decline in the region, it means things are finally looking up.

“It was going really bad.” says Einar Runar Sigurdsson, 49, a former sheep farmer turned mountaineering and glacier guide. “When I was a boy, there were around 100 people living here and 18 kids in the school. But the young people stopped wanting to take over the sheep herds and the old people started moving into seniors’ homes in bigger towns. Losing two generations at the same time left us with a lot of abandoned farms and we were down to about only sixty people.”

But then the Icelandic tourism boom happened. And that changed everything.

(Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

From Coast to Mountains, the guiding business run by Sigurdsson and his wife Matthildur Unnur Thorsteinsdottir, 47, took off, and they also opened a small cafe. Hotels opened. The demand became so great, Sigurdsson and Thorsteinsdottir’s son Aron, 27, also started running his own business, Local Guide, and hired around a dozen people.

And the domino effect is continuing to this day.

“The students in the school are the kids of the families running the hotels or working in the tourist business.” Thorsteinsdottir says. “More and more young families are building their houses or buying farms here so we’re now probably back up 80 or 90 people. Things are changing a lot and I’m so happy.”

The explosion of Iceland’s tourism industry has created well-documented social and environmental challenges for the country – particularly in the Reykjavik capital region and the so-called Golden Circle, a route near Reykjavik that holds many of the country’s major tourist sites.

But in the countryside, particularly in southeastern Iceland, tourism is more than just headaches and hassle.

It’s meant a rural revival.

(Thorvaldur Orn Krismundsson / AFP / Getty Images)

“Nobody wants to take over the farms.”

In recent years, Iceland, like pretty much every part of the world, has experienced a stampede of rural out-migration.

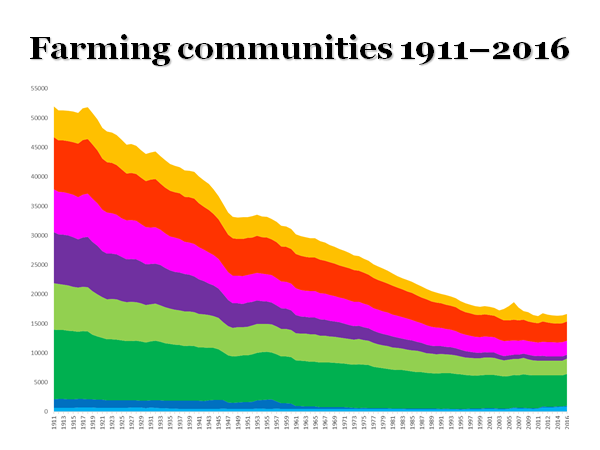

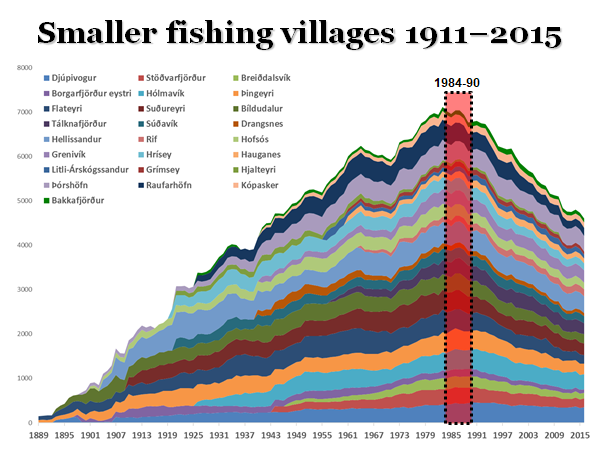

Historically an agricultural society, the majority of Iceland’s villages and towns didn’t even exist until the early 20th century. It wasn’t until the early 1900s, during Iceland’s era as a fishing powerhouse, that small towns and villages began mushrooming up along the island’s coasts, taking Iceland from one of the poorest and most rural countries in Europe to one of the most affluent.

But as technology advanced, the need for agricultural workers went down and farming communities went into steep decline. Then, by the 1970s, the fish stocks had crashed. Subsequent policies giving fishing quotas to companies, rather than the fishing villages or the fisherman that lived in them, seemed inadvertently designed to engineer people out of small communities.

(Courtesy Einar Runar Sigurdsson)

The demographic changes in Iceland were particularly acute because they disrupted a symbiotic relationship where the farms relied on the fishing villages for services like stores and schools; while the fishing villages relied on the farms for labour, meat and wool.

In short, when the fishing villages tanked, they took the farming communities with them.

“The balance was getting more and more tenuous and as a result, the farming population went down extremely”, says Thoroddur Bjarnason, a sociologist at Iceland’s University of Akureyri who specializes in regional development.

“You had these villages that were getting more and more desperate. They were losing young people, losing women and the average age was going up every year. But then tourism comes into play and a lot of interesting things start happening.”

(Courtesy Thoroddur Bjarnason / University of Akureyri)

A picture changes everything

Einar Runar Sigurdsson looks back at his family’s days in agriculture with a mixture of humour and bewilderment. He admits he wasn’t much of a farmer and got into tourism by accident. In 1989, his father, Sigurdur Bjarnason, decided it wasn’t possible to support a family with farming in modern Iceland and sold his sheep quota.

But Bjarnason was able to generate income by taking the occasional tourist to visit a puffin colony near the farm.

(Courtesy Einar Runar Sigurdsson)

Over time, Sigurdsson began to help out and also work as a mountain guide taking tourists to Hvannadalshnukur, Iceland’s highest peak.

“It was perfect.” he says. “Mountaineering gave me the opportunity to stay here and have year-round employment. Even though before the tourism boom there wasn’t a whole lot of income, especially in the winter.”

But then came Instagram, and that changed everything, he says.

“In 2010, winter started to become a bigger season. Photographers started coming to see the northern lights and I started taking people to see the ice caves too. Some of my clients’ photos went viral on Instagram and other social media. So then more and more photographers started calling and saying ‘Can you take us too?’”

(Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

The surge in tourism was enough to bring Sigurgeir Thoroddsen, 27, back to the region even after spending most of his life in the town of Mosfellsbaer and in Reykjavik.

He moved back into Fagurholsmyri, his grandparents old farm, and now works as a glacier guide, taking tourists to the Vatnajokull glacier with Local Guide, the company opened by Sigurdsson’s son Aron.

“We’ve sold our sheep quota and turned more to tourism but in the end, it’s still our farm.” Thoroddsen says. “I’ve always loved it here, it’s just that before there wasn’t any economic future.”

Pride in community

Gudrun Thora Gunnarsdottir, director of the Icelandic Tourism Research Centre in the city of Akureyri, says Iceland is facing serious tourism challenges, but that the positive impacts of tourism, particularly in rural areas, needs to be acknowledged and researched further.

“With the decline in both agriculture and fisheries, for a long time, the only things in the media about these communities were negative. But all of a sudden, tourism reversed this. Suddenly there was something interesting and dynamic going on in these places. That changes both the community itself and how the people from those communities perceive themselves.”

Tourism has also created opportunities in rural Iceland that previously would have only been available in places like Reykjavik, she says.

“Before in these communities you would know which family was in fisheries and which family was in agriculture. And for younger people, the only option was to go into the family business or leave the community. But the entrepreneurship around tourism has completely broken up those old models and that’s one of great benefits for rural areas when tourism development takes place.”

(Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

The Sigurdsson -Thorsteinsdottir family says they’re not sure all their three sons will end up staying on the farm, but they hope that the possibilities created by tourism in their community and others like it will at least let children in rural Iceland know that it’s possible.

“I sometimes hear my neighbours telling their children ‘There’s nothing here, you better go and get higher education and go to another country for your career’.” says Sigurdsson. “But I always tell my children that living here is privilege. I mean, people are coming from all around the world – places like Asia, North America, the Middle East – to see the place that we live. That makes me feel so satisfied.”

Helen Maria Bjornsdottir, 28, Sigurdsson’s daugher-in-law says, she hopes she can pass on the same enthusiasm to her children as well.

“We have a three-year old son we are already training him to be a glacier guide.” she says. “We hope he’ll end up running the family business one day.”

Marketing the North

RAUFARHOFN, Iceland

Dwarves…

Norse mythology…

Ancient viking gods…

They’re not the first things that come to mind when most people think of the Arctic.

But before you laugh, the residents of this remote Icelandic village would like you to know one thing: after years of neglect by the South, Odin the God of War, may very well end up doing more for their economy than the Reykjavik political class ever has.

“The herring went away and maybe they forgot about us.” says Jonas Fridrik Gudnason of the current state of Raufarhofn since the fish stocks collapsed in the late 1960s taking the village’s economy with it.

“So of course our project is a little bit crazy. But it has to be. We need something crazy to make people come up here.”

From boom to bust

Raufarhofn is located on the top end of Melrakkasletta, a peninsula stretching up towards the Arctic Circle in northeast Iceland.

(Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

During the country’s herring boom in the first half of the 1900s, Raufarhofn was an important port, home to 11 fish processing and salting stations, and up to 2000 residents during some periods. People in the region still speak with pride about those years, describing the village as one of the most valued harbours in the entire country.

But after the herring stocks collapsed, Raufarhofn never recovered.

Now home to less than 200 people, Arctic Henge may be the community’s last big economic hope – as long as they can convince the South to buy in on completing it.

The little project that could…

Arctic Henge, known as Heimskautsgerðið in Icelandic, is a community-driven tourism project inspired by Icelandic folklore and featuring a sprawling, photo-ready landscape reminiscent of England’s Stonehenge.

(Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

Based on Völuspá (The Wise Woman), an old Norse poem describing the world’s creation and presenting such characters as a seer, Odin the God of War, and a cast of dwarves so staggering it’s hard to keep track of, Arctic Henge features a series of massive arches made of old volcanic rock set up to catch sunlight at specific angles like a giant sundial.

The project was the brainchild of Erlingur Thoroddsen, a local hotel manager, who thought the big monument was just the thing to put Raufarhofn back on the map – both economically and in the national consciousness. Thoroddsen first had the idea in 1998 and pushed the project through all manner of fits and starts, including the 2008 financial crisis, until his death in 2015.

Gunnar Johannesson, an Arctic Henge board member, describes Thoroddsen as “ahead of his time” in fusing Icelandic culture and history with the Instagram-worthy photo possibilities that have helped drive Iceland’s tourism boom in the South.

“He had such ambition for the community and saw potential where no one else did.” Johannesson says. “We lost a lot when he passed away.”

(Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

But the region’s remote location, and lack of transport and tourism infrastructure, means Arctic Henge struggles to rally consistent financing from the government and funding bodies in the South.

It’s a situation that clearly baffles Johannesson, who says he supports the project even through he lives in an entirely different town, because he believes Arctic Henge will benefit the entire region.

“There’s a tendency for the South to look, not just at our project, but any project in the North, as not worth it, as serving too few people.” says Johannesson, who’s based in Husavik, a town of approximately 2000 people, 140km southwest of Raufarhofn, where he manages the Travel North agency.

“But we should be turning those conversations around. Communities like Raufarhofn are starting to fade but they deserve to be built up after what they contributed to Iceland during the herring years. That’s why the nation should give this idea, and others like it, support.”

(Courtesy Thoroddur Bjarnason / University of Akureyri)

Though Arctic Henge is open to the public — even on the coldest, greyest days one or two photographers can usually be found prowling the grounds searching for the perfect image — the project is technically unfinished.

Around 40 million Icelandic kronur — ISK, ($520,000 CDN), has come through this year so the parking lot, a path and a bridge can be completed this summer. But another 110 million ISK ($1.4 million CDN) is still needed to finish the monuments and landscaping, get electricity and running water to the site, and finish off things like the all-important dwarf sculptures.

The uncertainty is palpably frustrating to board members — some who’ve been volunteering their time, energy, and paying things like project-related travel expenses out of pocket, for up to 15 years.

“In Iceland everything is very complicated, very long, very expensive and requires endless, endless, endless, endless, endless paperwork.” says Gudnason. “But we keep at it like a bad habit.”

The North & the ‘everything-outside-of-Reykjavik’ divide

But the challenges faced in developing a tourism project like Arctic Henge aren’t unique to Raufarhofn. They’re shared by many small Arctic communities no matter what country they’re in.

(Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

How do you exploit spectacular nature, when the only roads to get there are underdeveloped, seasonal or even non-existent?

How do you encourage people to visit your region when there are no hotels, restaurants or other tourism infrastructure to accommodate them?

And maybe most importantly, how do you even get people to the North in the first place when it’s often cheaper to fly to places like London or Paris than it is to fly to the Arctic, even when it’s in your own country?

Marketing the North

The problem isn’t that Iceland’s North is without sites.

Statistics from Visit North Iceland, the marketing arm for this region, show half the people that visit Iceland during the summer come North to visit Akureyri, the biggest city in Iceland’s North, and Lake Myvatn, one of Iceland’s top attractions.

(Loic Venance / AFP / Getty Images)

But in the winter that number plunges to around 11 per cent.

And in 2017, only 35,000 of Iceland’s 2 million visitors made their way up to the Melrakkasletta peninsula, where villages like Raufarhofn are located.

“If you look up what’s talked about in the media, it’s always how Iceland is full and overcrowded.” says Arnheidur Johannsdottir, managing director of Visit North Iceland. “But that only affects about 5 per cent of the destinations. The rest of the country is happy to welcome more people.”

“Tourists only want Reykjavik because they think there’s nothing interesting to see in the North, but that is so, so wrong. We have the beautiful scenery, just like the South, but we also have what I’d call ‘the Arctic way of life’, being close to nature and community.”

To help promote the region, Visit North Iceland is launching a major project called the Arctic Coast Way in 2019. The 800km route will stretch across north Iceland and is being marketed as an off-the-beaten-track route that will take visitors through 21 of some of the country’s most remote villages.

All that needs to be done now is to make it easier, and more reasonable, for people to get up to the North in the first place.

Iceland, a country? Or just a city called Reykjavik?

One of the key challenges this region faces is shared by many places in the circumpolar world whether in Canada, Alaska or Europe: trying to convince remote southern capitals that investment in the North is worth it.

(Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

“We’re always working on these issues.” says Johannsdottir. “We have so much to offer, but if people can’t afford to even get up here, that’s a hurdle. We need to lobby politicians for better roads and transport, reasonable flights, and to make sure that people understand these things are important not just for northern communities , but for everyone.”

“It’s all part of a bigger national discussion that we’ll have to have at some point: do we want Iceland to be an actual country or just a city called Reykjavik? Because if we don’t invest in our smaller communities, that’s what will happen.”

It’s not like there’s no precedent in Iceland for the transformative power of new infrastructure in the North.

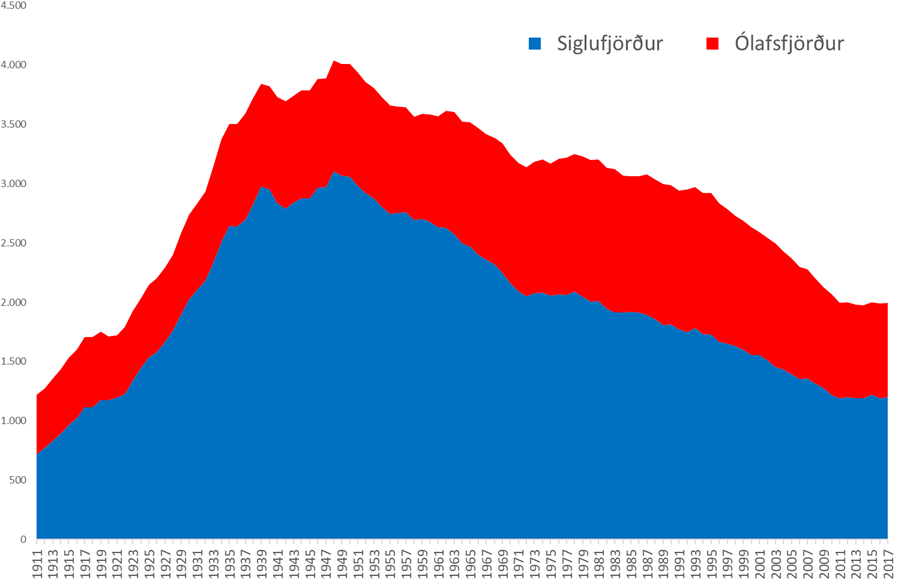

The village of Siglufjordur, located on Iceland’s north coast, was also economically decimated by the end of the herring industry and lack of an all-weather road. But that all changed when the 12 billion ISK ($155 million CDN) Hedinsfjardargong mountain tunnel project opened in 2010, finally connecting the village to Iceland’s main transportation networks.

(Courtesy Thoroddur Bjarnason / University of Akureyri)

The tunnel project also prompted local businessman Robert Gudfinnsson, head of the board of directors of biotech company Genis, to invest 4 billion ISK ($52 million CDN), mostly from his own personal fortune, into developing Siglufjordur, turning the dying village into a prosperous community with a thriving tourism industry and diversified economy – all because people could finally get to it.

Getting the North on the tourism radar

Gudrun Thora Gunnarsdottir, director of the Icelandic Tourism Research Centre and based in Akureyri, says the North needs to be integrated into a wider tourism strategy, something she says would help distribute travellers more evenly throughout the country and ease tourism bottlenecks in the South.

(Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

“Tourism is a very complicated phenomenon, you have issues related to environment, to culture, to education to infrastructure– it touches everything in society and needs a holistic approach.” Gunnarsdottir says. “But Icelandic political and decision-making structures were set up to govern a fishing and agricultural society that doesn’t exist anymore – not something like mass tourism bringing 2 million people a year into a country of 330,000.”

“We’re gradually seeing changes but investing in a road in the North is still seen in old terms: as building a road for a small village no one goes to, not as investing in a road that will help develop tourism and diversify the economy in our northern communities.”

As for the folks back in Raufarhofn, they hope any integrated tourism strategy will take their village, and others like it, into consideration, but while the politicians are at it, can someone, somewhere, just help them get Arctic Henge finished once and for all?

“I thought we’d be long done with this, but I’m an old, grumpy, retired man and still at it.” says Raufarhofn’s Jonas Fridrik Gudnason. “We may seem like just a few silly people way up here, but we can’t stop now. We have to finish what Erlingur started.”

(Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

About

Eilís Quinn is a journalist and manages Radio Canada International’s Eye on the Arctic circumpolar news project. At Eye on the Arctic, Eilís has produced documentary and multimedia series about climate change and the issues facing Indigenous peoples in the circumpolar world. Her documentary Bridging the Divide was a finalist at the 2012 Webby Awards. Eilís began reporting on the North in 2001.

Her work as a reporter in Canada and the United States, and as TV host for the Discovery/BBC Worldwide series Best in China, has taken her to some of the world’s coldest regions including the Tibetan mountains, Greenland and Alaska; along with the Arctic regions of Canada, Russia, Norway and Iceland.

Twitter : @Arctic_EQ

Email : Eilís Quinn