Sister Wanda Robson picked up fight for justice more than 6 decades later

By Asha Tomlinson, CBC News

Wanda Robson becomes very emotional when she thinks about what her sister — Canadian civil rights icon Viola Desmond — would tell her if she were alive today.

“She was something else … I loved her.”

Robson, now 89 and living in North Sydney, N.S., has continued to keep her sister’s legacy alive by speaking to students, doing media interviews and writing books about her family’s experience after Desmond refused to leave the whites-only section of a theatre in New Glasgow, N.S., in November 1946.

Viola Desmond was a quiet revolutionary — a title also used to describe another civil rights icon in the United States, Rosa Parks. But Desmond’s act of defiance happened nine years before Parks refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Ala.

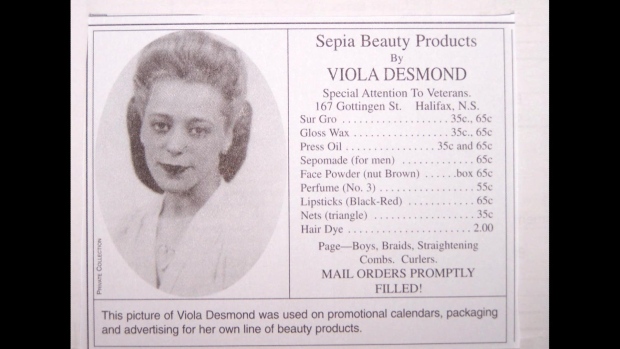

In Desmond’s case, she just wanted to see a movie at the Roseland Theatre. Instead, the 32-year-old beautician and businesswoman, who had some time on her hands while her car was getting fixed, was thrown out of the theatre and straight into jail.

Ostensibly, she was removed because she failed to pay a one-cent tax, even though she offered to pay the difference.

There were segregation laws in place and black people could only sit in the balcony of the theatre. Desmond realized quickly she was being targeted because of the colour of her skin.

Robson vividly remembers that day in 1946 and how her sister described the ordeal.

“The usher came up and said, ‘Miss, you are sitting in the wrong seat, you can’t sit here, that seat is more expensive,’ so Viola said, ‘OK, I’ll go and pay the difference,'” Robson says.

“But when the usher came again and said, ‘I’m going to have to get a manager.’ Viola said, ‘Get the manager. I’m not doing anything wrong.’ ”

No escape

The manager dragged her out of the theatre and she was arrested. Badly bruised, she spent a night in jail and was released the next day after paying a $20 fine and $6 in court costs.

Desmond’s name was all over the newspapers. People were talking about it in New Glasgow and beyond. She couldn’t escape what happened. Neither could her family.

Some people supported her courage but others felt she should have accepted the segregation laws and sat in the black section of the theatre like everybody else.

Even Robson, who was 19 at the time, questioned her sister’s actions.

“People ask me: ‘What would you have done?’ Well, I would have been very angry but I would have gotten up with my head down … gone out and never come back,” says Robson.

Desmond was encouraged by community members, including her family doctor who treated her injuries, to hire legal counsel and appeal the charge in court. She also worked with the newly created Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People.

She lost that fight but her case led to the eventual abolishment of the segregation laws in the province in 1954.

The incident took a toll on Desmond over the years. She went through a divorce, shut down her business and moved to Montreal and New York City for a fresh start and new opportunities. In 1965, she died alone in the U.S. at the age of 50 from internal bleeding.

Picking up the crusade

Decades after her death, realizing how important it was to share her sister’s story, Robson picked up the crusade for justice.

“Every time I spoke about Viola, the full meaning of what she had done, her act, really hit me.”

In 2009, Robson wrote a letter to the mayor of New Glasgow and asked town council to pass a motion acknowledging the incident. That request went up the ranks to the premier’s office and in 2010, 63 years after her conviction, the province posthumously awarded Desmond an apology and pardon.

“I wrote to the mayor thinking that nothing would come of it,” Robson says. “Next thing you know … the injustice was brought forward and she was granted this pardon. So now it has come full circle, this whole act, my sister and the pride that goes with it.”

Mayann Francis, the first black lieutenant-governor in Nova Scotia,issued the free pardon.

“The free pardon is based on innocence. Viola Desmond was innocent. It was a very moving experience for me knowing that I was the one, a black woman, who was going to be giving Viola Desmond something she should have had a long time ago … her freedom,” says Francis.

“I remember my heart was beating away … there were so many cameras and I kept thinking: ‘This is for you, Viola.’ ”

Click here to read more on CBC.ca

Great article.

There were segregation laws in place and black people could only sit in the balcony of the theatre. Desmond realized quickly she was being targeted because of the colour of her skin.