Its called schistosomiosis and it affects more than 200 million people worlwide. It’s common in Asia and South America, but most cases are in sub-Saharan Africa.

It’s a chronic disease, in which a small parasite enters the skin and develops into a worm that ultimately infects the blood vessels near the intestine or bladder.

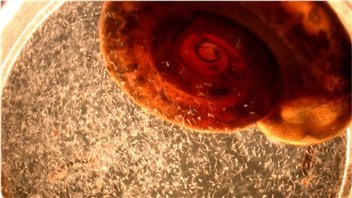

The parasite uses a species of small snail as its mid-stage host for its larval development. The parasites grow in the snail which becomes a factory releasing them into the surrounding water.

Once they contact human skin, the tiny parasites enter the blood stream and grow into worms, eventually causing chronic health issues particularly in the liver, bladder and urogenital tract. Eggs are passed from the human, hatching into a different free-swimming stage that seeks out and infects the snails, and the cycle is repeated.

At the University of Alberta, professor Patrick Hanington, who specializes in infectious diseases, is one of a relatively limited number of researchers working on ways to break the cycle.

It’s considered to be the second most widespread parasitic disease in the world, after malaria.

Although not immediately deadly, it is a chronic disease which can lead to many later complications, including cancer of the liver and cancer of the bladder. Infections of the urinary tract and vagina can promote the spread of HIV. In children, it can lead to motor skills and intellectual development problems.

Presently, the typical treatment is to kill the worms in those affected by administering a particular drug. While this is effective in killing the parasite, it does nothing to prevent re-infection.

Dr. Hanington and several others around the world are studying ways to break the cycle of infection. He is studying the immune systems of the particular snail species to find out why some snails of the host species are immune to the parasite, while others are not, and also why that does not seem to give the resistant snails a survival and propagation advantage over susceptible snails. He is also looking into possible genetic manipulation of the snails.

The World Health Organization (WHO) is behind a movement to find a solution by the year 2025. Dr Hanington says it is an important effort, as there is some concern that the parasite is beginning to develop resistance to the sole drug currently effective in killing the worm in infected people.

RCI’s Marc Montgomery spoke with Dr Hanington at his office in the School of Public Health at the University.

Listen

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.