Many people remember disastrous ocean oil spills such as the 1989 Exxon Valdez supertanker incident in Alaska, and of course the 2010 BP drilling disaster in the Gulf of Mexico.

sticks to surfaces, sand, rocks, plants, shells animals. etc,

it become extremely costly and time consuming to remove

© Eric Gay/Associated Press

A major part of the problem is that cleanup becomes extremely difficult and costly once the oil sticks to a surface, whether that be rocks or sand or plants, birds or the sea floor and marine life.

Canadian engineering researchers at the University of Alberta in Edmonton have developed a promising way to help with clean ups.

While study of how petroleum sticks to various materials on land is relatively easy, trying to study this in a marine environment, ie under water, is very complex.

In trying to develop techniques to perform such underwater studies Professor Sushanta Mitra and his team which includes Prashant Waghmare, and Siddhartha Das, developed a simple material that repels oil, creating a barrier and preventing it from coming into contact with surfaces underwater

In very simple terms, Dr Mitra and his team,they created a “super-soap”. Soap contains surfactants, which have molecular chains which on one end attract oils and repels water, and on the other, attract water molecules and repel oils.

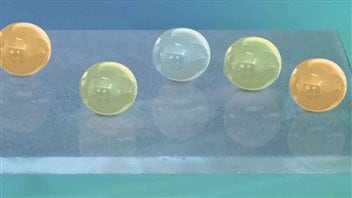

the surfactant treated surface repels the oil from the glass surface

© Dr S Mitra

This enables soap and grease or oil to bind together and yet be easily washed off things like your dishes or hands. Dr Mitra and his team played with the surfactant molecules to create a new material which does stay on surfaces underwater, but will not bind with oil, and actually repels it from the surface of material, which in the case of their experiments was a simple sheet of glass.

While still at a highly experimental stage, the University of Alberta team feel this has potential for development into materials and processes to prevent major damage to marine and shoreline ecosystems and fauna.

Dr Mitra says spraying shorelines, or coating marine ecosystems with the surfactant could prevent massive harm to the environment from the oil while also reducing the astronomical costs and time required to clean up after oil spills.

Studies have shown that the dispersants used by BP in the Deepwater-Horizon spill were in fact highly toxic. Although in this early stage no studies of toxicity or effects on marine plants and animals, Dr Mitra and team feel there is likely to be little negative effect, or certainly far less detrimental than those dispersants or the oil itself.

of surfactant formula on oil © courtesy S Mitra

While engineers are experimenting with highly sophisticated and expensive surface materials, designs and even nano-technology to prevent petroleum from sticking to surfaces such as ships, Professor Mitra suggests this development might prove to be a much simpler and far lower cost development.

Science journal “Soft Matter”: (abstract) Drop deposition on under-liquid low-energy surfaces

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.