Led by researchers in Edmonton Alberta, technology has shown for the first time that there are developmental differences between the brains of people who stutter and those of non-stuttering people.

Deryk Beal is Executive Director at the Institute for Stuttering Treatment and Research (ISTAR) and Assistant Professor, Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders, Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine at the University of Alberta in Edmonton.

Listen

This was the effort involving the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to study brain development from childhood to adulthood. The brains of both normal speakers and males who stutter ranging in age from 6 to 48 were involved.

Males were studied as they outnumber females about five to one with respect to persistent stuttering. Some 116 subjects were studied, roughly half were people who stutter, with the other half used as a control group in the largest group and widest age-range for such a study.

The findings were published in the journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience

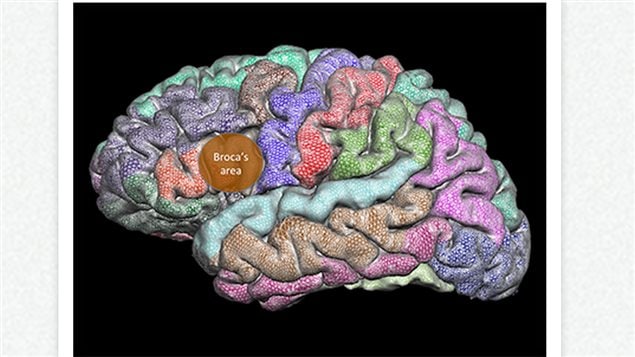

Professor Beal and his team, which included collaborators from the University of Toronto, found a specific area in the brain, Broca’s Area, that did not develop the same way in people who stuter compared to normal speakers.

“In every other region of the brain we studied, we saw a typical pattern of brain-matter development. These findings implicate Broca’s area as a crucial region associated with stuttering,”

The study found that the cortical thickness in the Broca’s area develops abnormally in those who stutter.

The Broca’s area is the region of the brain responsible for speech production coordinating signals that result in motor commands to the mouth and tongue etc.

However, scientists still cannot say definitively that Broca’s region is responsible for stuttering.

“It’s like the chicken and the egg,” Beal explained. “We don’t know if the changes we are seeing in this region of the brain are the result of a reaction in the brain to stuttered speech or some other difference in how the brain is operating elsewhere, or indeed if these changes are the cause of the disorder.”

Professor Beal says that what is needed now is a long-term study of brain development from infancy to adulthood to look at how brain growth in speech areas differs between children who stutter, those who don’t, and kids who stutter but later recover naturally or with treatment.”

Funding for this research came from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) with additional funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the SickKids Foundation

The clinical programme at the Institute for Stuttering Treatment and Research (ISTAR) also receives generous funding from the Elks and Royal Purple service clubs.

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.