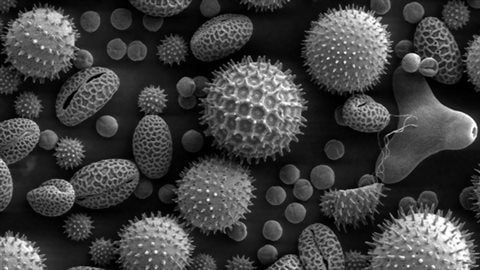

Some people suffer through spring and all its pollen with clogged noses, and runny and itchy eyes. Others can’t be near cats, others can have potentially deadly reactions to peanuts or seafood.

It seems between 20-30 percent of the Canadian population suffers from an allergy within a range of these reactions, with about one in 13 Canadians suffering a food allergy.

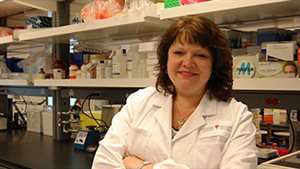

However, in the future people may be free of such reactions thanks to research supervised by Dr Christine McCusker (MD, MSc, FRCP) and her lab.

She is an allergist at the Montreal Children’s Hospital and researcher at the RI-MUHC and associate professor in the Department of Pediatrics at McGill University

Listen

The research was published in the science journal Mucosal Immunology entitled, “TGF-ß-Mediated Airway Tolerance to Allergens Induced by Peptide based Immunomodulatory Mucosal Vaccination”

Dr McCusker says everyone has a reaction to allergens, but that people’s bodies react in different ways. Most people’s immune systems identify the foreign entity in the body as not being a threat, and as such initiate no defensive response. In people with allergies however, the opposite is true.

Allergies can develop very early in childhood and are usually life-long with no real cure at present.

It is thought that all children are born with the potential to develop allergies, but in most, the shift to non-allergic reaction to a majority of pathogens occurs fairly early in development. Children who develop allergies have not made the shift prior to exposure to allergenic agents.

The researchers sought a way to “teach” the immune system, or re-direct it not to over-react to simple allergens such as pollen or cat hair (dander) for example.

The research goal was to develop a method which did not hinder the immune system in any way, so that it would still function to protect the body from viruses and harmful bacteria, but to redirect it’s reaction to potential allergens. In other words to teach the body not to over-react to essential harmless allergens.

What the research team developed was a molecule, specifically a peptide or small bit of a protein, that mirrors the “inflammatory” response. When this mirror peptide is in the body, it stopped the body’s own over-reacting response.

They further found that after a short trial period, the immune system “learned” that allergens were not serious threats and so the inflammatory /over-reaction no longer occurred even without the added peptide.

As the tests also showed that because the over-reaction was stopped before it began, there was no allergic reaction at all, so no range of reactions from mild to extreme, they are now testing the process on food allergies which often have very extreme reactions.

An additional benefit in this early stage seems to point to additional benefits in terms of an improved reaction to actual infections such as influenza by also blocking unnecessary overreaction.

The work focussed on the molecule known as STAT-6 which in important in the body’s allergy response. The peptide developed is known as STAT-6 IP

By giving the peptide STAT6-IP very early on, before allergies are present, we were able to teach the immune system. So when we tried to make the mice allergic later on, we couldn’t because the immune system had ‘learned’ to tolerate allergens,” explains Dr. McCusker.

The tests have been performed on mice with this peptide delivered as nose drops. By delivering the peptide early in life, the mice immune did not over-react when various allegens were introduced later. Thus their bodies “learned” and so they would not develop allergies at all.

It is hoped that this means that in the future, allergic response might be eliminated by giving a vaccine or nasal spray very early in a child’s life.

“What’s beautiful about our approach is that you do not have to couple it with a specific allergen, you only use this peptide. It just redirects the immune system away from the allergic response and then it will not matter if the child is exposed to pollen, cats or dogs, because the immune system will not form an aggressive allergic reaction anymore,” adds Dr. McCusker.

The study was co-authored by H Michael, Y Li, Y Wang, D Xue, J Shan, BD Mazer and CT McCusker from the Meakins-Christie Laboratories, McGill University and Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

This research was made possible by funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre (RI-MUHC), the Montreal Chest Institute and the Strauss Family Foundation, JTCostello Memorial Research Fund, the Fonds de Recherche du Quebec-Santé (FRQS), and the Montreal Children’s Hospital Research Institute.

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.