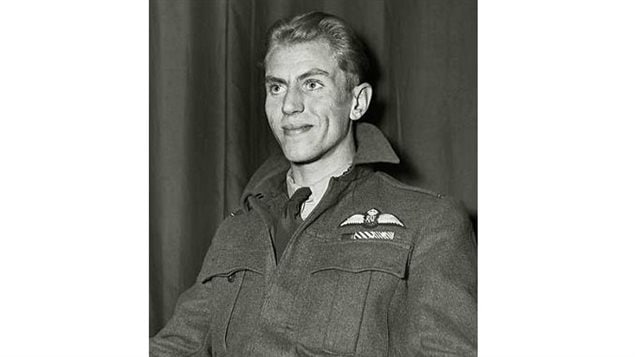

George Beurling DSO, DFC, DFM & Bar was only 26 at the time of his death on May 20, 1948.

Unlike most flying aces of either of the world wars, Beurling is largely forgotten today in spite of the fact he was Canada’s highest scoring ace of the Second World War.

The reason perhaps is that he didn’t quite fit the mould of a hero.

In America, he might have had movies filmed about him; good looking, unruly hair, unconcerned about spit and polish and disdainful of authority and rules, a bit of a loner, a “rebel”, but superb at his craft. That may be how they like them in the Hollywood movies, but it didn’t work in Canada, or the Commonwealth.

Born in Verdun, now a suburb of Montreal, Beurling tried to join the RCAF at the outset of war. He was turned away due to a lack of schooling, having quit high-school early to fly for a commercial operation.

In 1940 after a failed bid to join the Finnish Air Force fighting the Russians, he managed to get accepted into the RAF flight school.

One of his instructors Ginger Lacey, an ace himself, later said, “There are not two ways about it, he was a wonderful pilot and an even better shot.”

But, Beurling didn’t drink, didn’t smoke, was religious, and didn’t socialize much with others. He wasn’t immediately popular. He was much more concerned about developing tactics and shooting techniques.

He also was not much for obeying authority or rules and constantly irritated his superiors.

He soon was being nicknamed either “Buzz” for his low level antics- rumoured on one occasion to have flown under a low bridge, or “screwball” for his attitude toward regulations, formation flying, and also because it was one of his favourite expressions.

Although recognized for his outstanding skill, he was not particularly liked by his mates nor officers, and when he requested a transfer, it was quickly granted.

He ended up in Malta which was under constant air attack by German and Italian forces.

It was here that Beurling came into his own, quickly demonstrating his superiority.

His score against enemy planes grew quickly, as he developed his technique. He wasted few bullets and generally got within very close ranges, 250 yards, before firing short bursts with deadly effect.

In one 14-day span on Malta he shot down 27 enemy planes. To escape pursuing planes, he also developed evasive techniques that few would dare, quite literally throwing his Spitfire into impossible stalls and spins which the enemy simply couldn’t follow.

Because of his score, he was awarded medals and promoted. As Canada’s top fighter ace, he was sent back to Canada on a Victory Bonds promotional tour.

It was a disaster.

He did not like the spotlight as a hero, and shocked audiences by describing his dogfights and saying he enjoyed killing the enemy.

“I came right up underneath his tail. I was going faster than he was; about fifty yards behind. I was tending to overshoot. I weaved off to the right, and he looked out to his left. I weaved to the left and he looked out to his right. So, he still didn’t know I was there.

About this time I closed up to about thirty yards, and I was on his portside coming in at about a fifteen-degree angle. Well, twenty-five to thirty yards in the air looks as if you’re right on top of him because there is no background, no perspective there and it looks pretty close. I could see all the details in his face because he turned and looked at me just as I had a bead on him.

One of my can shells caught him in the face and blew his head right off. The body slumped and the slipstream caught the neck, the stub of the neck, and the blood streamed down the side of the cockpit. It was a great sight anyway, the red blood down the white fuselage. I must say it gives you a feeling of satisfaction when you actually blow their brains out.” November 1942 Verdun Arena Victory Bond speech

Now a member of the RCAF, he was sent back to England where he continued to get into trouble, including stunt flying, perhaps to relieve his own boredom with routine aerial sweeps. He was transferred back to Canada as a ferry pilot, but in 1944, with no one willing to send him back to combat, he resigned.

He ended his war with 31 ½ kills, the highest score of any Canadian.

He didn’t fit well in civilian life and in 1948 offered to fly P-51 fighters for Israel. The Canadian government disapproved of what it saw was acting as a mercenary.

Britain also disapproved, tied as it was to the Arab cause and actuatlly fighting against Israeli “terrorist” acts.

Beurling may have spoken a little too loudly and often about his plan.

After arriving in Rome, he and another pilot, Len Cohen, took off to test fly an Israeli marked Norseman.

The date was May 20, 1948.

As it approached for a landing, witnesses saw flames from the engine and the plane exploded upon touchdown burning the two pilots to death.

Was it an accident as the official investigation said, or perhaps sabotage by Britain or by Arabs to prevent a highly skilled fighter pilot from aiding the Israeli cause? Or was it Italians acting in revenge for his wartime score which included many Italians?

Adding to the mystery was the fact that Canada never claimed the body of its top scoring ace of WWII.

After storage in a warehouse for three months (as no-one claimed the body), the young man’s ex-wife had his body buried in a Rome cemetery between the graves of Percy Bysshe Shelley and John Keats.

Though he never actually fought for Israel, in 1950, authorities there had the body flown to Haifa and then moved to a military cemetery at the foot of Mount Carmel.

In Canada he is remembered in Verdun with a small street now named Rue Beurling along with a small park, and sadly not much else.

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.