The first language you hear as a baby, even if only for a very brief period, seems to “hardwire” your brain. New research from McGill University and the Montreal Neurological Institute shows that traces of early speech recognition patterns remain even many years later.

Fred Genesee (PhD) is professor Emeritus in the Department of Psychology at McGill University in Montreal and a co-author of the new study.

Listen

The study entitled ”Past Experience Shapes Ongoing Neural Patterns for Language” was published in the scientific journal Nature Communications.

This newest study builds on an earlier one in which Chinese-sounding words were tested on Chinese children who had been adopted from China as babies by French-speaking Quebec couples.

The children had not heard Chinese spoken since the adoption and had then grown up as monolingual French speakers.

In that study they were compared with fluently bilingual Canadian-born children of Chinese descent who learned to speak Chinese and then French. That study showed the adoptees’ brains, even though having no knowledge of Chinese, reacted similarly to the Chinese sounding words as those of the bilingual children.

In this latest research, three sets of children from the 10 -17 age group were tested: monolingual Quebec French-speaking students; monolingual French speakers who had been adopted from China as babies and had heard Chinese for the first 12-18 months of life and had grown up only learning French and fluently bilingual speakers of both Chinese and French.

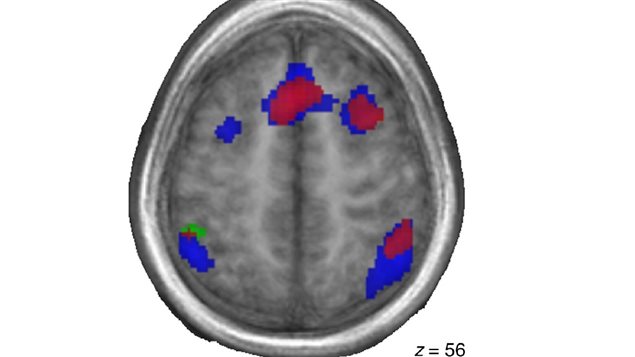

The groups listened to pseudo-French words (i.e., which sound French but are not actual words). As they listened, their brains were scanned by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to see which areas were activated.

All three groups recognized the sounds with equal results. The original presumption was that the monolingual native French speakers, and the monolingual adoptees would have similar scans. However, the adoptees had scans which were instead similar to those teens who were fluently bilingual, having learned Chinese first, and then French.

What this showed to the researchers was that the brain processing of language is established very early in development and traces of that established processing pattern remain for many years later.

It also showed the plasticity of the brain to use the original processing combined with new processing areas to produce a result very similar in ability to those monolingual native French speakers.

Lara Pierce, a doctoral student at McGill is the lead researcher for the study. She is quoted in a McGill news article saying, “During the first year of life, as a first step in language development, infants’ brains are highly tuned to collect and store information about the sounds that are relevant and important to the language they hear around them. What we discovered when we tested the children who had been adopted into French-language families and no longer spoke Chinese, was that, like children who were bilingual, the areas of the brain known to be involved in working memory and general attention were activated when they were asked to perform tests involving language. These results suggest that children exposed to Chinese as infants process French in a different manner to monolingual French children.”

The researchers believe that this knowledge would help in understanding and aiding children learning a new language. They will also continue this study to determine the activity and patterns in these groups while the brain is at rest. In an additional study, they will examine the brain activity and the differences in “relearning” the original language compared to those learning the second language for the first time.

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.