As the Liberal government embarks on its long-promised defence policy review, it has to take a serious look at the threats and challenges to Canada’s security and sovereignty in the Arctic, says an expert on Arctic security.

Rob Huebert, associate professor with the Department of Political Science and research fellow with the Centre for Military and Strategic Studies at University of Calgary, said that to a very large degree the manner in which the Liberals approach the Arctic will basically illustrate what they are trying to get out of this particular defence review, Huebert said.

“Defence reviews can be asking basic questions on what Canadian security should be, they can be a political document justifying a country’s direction, and they can be a paper exercise,” Huebert said in a phone interview from Calgary. “So I think that if the government is indeed intent on asking what we need to give Canada the best security in the future, they are going to have to feature a predominant amount of effort on understanding the emerging security environment in the Arctic. It’s just that important to Canada.”

On the other hand, if the Liberals focus on demonstrating at all costs their difference from the previous Conservative government, then they will minimize the role of the Arctic in their defence review, Huebert said.

It will really come down to how serious the Liberals are about the issues facing Canada today, Huebert said.

Changes in strategic security environment

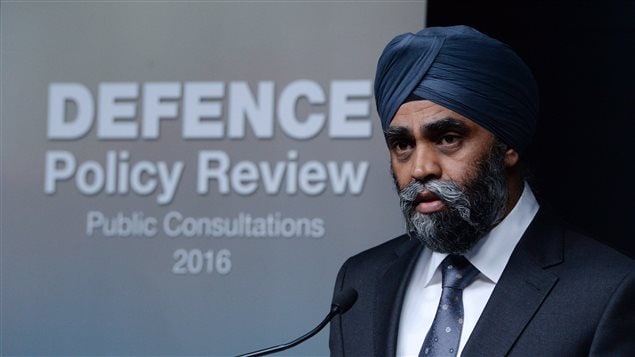

“The strategic security environment in which the Canadian Armed Forces operates has changed significantly,” Defence Minister Harjit Sajjan said in a statement as he launched the defence review process in Ottawa on Wednesday. “I look forward to hearing from Canadians, from coast to coast to coast, as they help inform the development of a modern defence policy that will support the CAF to effectively respond to a full spectrum of challenges – now, and into the future.”

Srdjan Vucetic, associate professor at University of Ottawa’s Graduate School of Public and International Affairs (GSPIA), said very little is known about the Liberal thinking on changes to the global security environment.

“You could argue that there has been a shift towards something like multi-polarity,” Vucetic said. “The so-called great power politics are back.”

Huebert said he expects some of that great power rivalry to spill over into the rapidly melting Arctic.

There is widespread acknowledgement that the entire Arctic region has changed in recent years, Huebert said.

“Climate change is the one that most people focus on, so the physical reality of the Arctic is changing, but more to the point, and I think this follows after what has happened in the Ukraine, is that people have realized that we do not have all of the community of nations that exist in the Arctic region, all basically on the same page,” Huebert said.

‘Arctic-powerful’ Russia

There is a growing realization that we are facing a much more “Arctic-powerful” Russia that does not necessarily share all of our security interests, he said.

“By the same token, I think there is a growing understanding that the Americans are becoming reengaged from a security perspective in the Arctic,” Huebert said. “And I dare to say the arrival of the Chinese naval task force in the Aleutian Islands last year and the visit of the Chinese naval vessels to some of the Nordic countries last year have also demonstrated that the Chinese from a strategic perspective are starting to become interested as well.”

The Arctic has become a much more complicated security environment involving the core strategic interests of some of the world’s most powerful countries, he said.

Despite this, there is a wide assumption among some analysts and decision makers that there is a normative good in the Arctic, that is somehow different from the rest of the world because its harsh environment forces circumpolar countries to pool resources and cooperate with each other, Huebert said.

“The problem with that is I think it really represents what we wish the Arctic was, rather than what it really has become,” Huebert said.

With few notable exceptions cooperation in the Arctic between circumpolar countries is nothing more than “cooperation about agreeing to cooperate,” Huebert said.

While acknowledging the success of the Arctic Council at some governance issues, the signing of the Coast Guard agreement, the cooperation on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), Huebert said it doesn’t change the geopolitical realities of the increasing complex and accessible region.

‘Security imperatives’

“There are several key security imperatives that the Americans and the Russians face in the Arctic that we ignore at our peril,” Huebert said. “They haven’t come to the forefront yet and they haven’t become a major issue yet, but because they are so important to both Russia and the Unites States, and because they will come into competition with each other, this is where the problem is.”

For the Russians it’s all about their nuclear stability, the nuclear deterrent, Huebert said. Russia has been rebuilding its nuclear capability with great focus on their submarine-launched missiles that are primarily based in the Arctic region, the Northern Fleet, he said.

“As the Russians resume their position as a great power, as they try to rebuild their nuclear deterrent, which becomes their number one security policy…, they are going to take steps to defend it,” Huebert said. “That’s why we’re seeing the additional new bases going up in the Arctic.”

American concerns

On the other side of the coin, the Americans are becoming increasingly concerned about the North Korean missile threat, which as some point could be extended to the Chinese missile threat, Huebert said.

“If you take a look at where they have placed most of their mid-range interceptors, it’s in Alaska, because geographically that’s the best place to intercept missiles coming from that side of Asia,” Huebert said.

At the same time, the United States continue to send their attack subs into the Arctic region to demonstrate their ability to conduct naval operations in the region, even if under the guise of “scientific expeditions,” he said.

“You start putting all that together and then overlay growing competition in places such as Ukraine, Georgia, what the Russians call the ‘near abroad,’ the coming competition between the Americans and the Chinese and you can see the growing importance from a strategic perspective that the Arctic will have,” Huebert said. “And this is something, of course, if we are truly trying to look into the future of what to do, this is what we have to be examining.”

Surveillance capability

This new threat environment forces Canada to improve its surveillance and response of capabilities to maintain its sovereignty in the Arctic, Huebert said.

Ottawa has to take a hard look at what are some of the tools that Canada as an Arctic nation need in this environment to be able to adequately provide for the security of the region, Huebert said.

One such area is the continued funding for the continuance of the RadarSat system that gives Canada a very good surveillance capability in the Arctic, he said. Canada also needs to invest in ship identification systems, Arctic offshore patrol vessels and subsurface surveillance capabilities.

“We also have to be looking at our relationships with our northern allies,” Huebert said. “To that degree one of the major issues we will be facing, is how do we modernize NORAD.”

NORAD’s North Warning System was last given a major update in 1985, he said.

Ottawa also has to find a replacement for the ageing Canadian CF-18 fighter jets that provide the enforcement element of the North Warning System, a politically sensitive task for the Liberal government, which cancelled the F-35 program, Huebert said.

If Canada doesn’t come up with a timely replacement for the CF-18s, it might have to ask the United States to take over that role in protecting the northern flank of the North American continent, which would mean a significant surrender of Arctic sovereignty, Huebert said.

Increased NATO role in the Arctic?

Canada will also have to resolve its disagreement with Norway over Oslo’s desire to see increased NATO involvement in the Arctic, which the Harper government had opposed fearing erosion of sovereignty in the Arctic, given the stance of many European Union countries on the legal status of the Northwest Passage, which Canada considers internal waters, but the United States and several other countries see as international waters, Huebert said.

Another potential security and diplomatic dilemma for the Liberals is the possibility of Sweden and Finland, increasingly concerned with Russia’s assertive foreign policy and the militarization of the Arctic, asking to join the NATO.

“If that happens, it has all sorts of ramifications for Canada,” Huebert said. “If we say ‘no,’ it’s going to look as if we’re being intimidated by Russia. If we say ‘yes,’ I doubt that the existing multilateral cooperation that so many people are so justifiably proud of, such as the Arctic Council, how realistic is to expect that to continue.”

The most fundamental issue that gets very little public discussion is the lack of realization that the global security environment is once again becoming dangerous well beyond the much publicized threat of terrorism, Huebert said.

No friends, only interests?

“I think the other question too is this ongoing assumption that we can always count on the support and the assistance from our closest friends and allies,” Huebert said. “Within international relations there is the ongoing cliché that people have friends but countries only have interests. You watch some of the peculiar things happening in the United States right now from a political perspective and you go, ‘I don’t if you can necessarily count on this ongoing special relationship always ultimately protecting Canadian interests.”

For example a Trump presidency is very likely to question a lot of the assumptions in terms of the benefits the United States gets out of supporting its allies, Huebert said.

“Listen to some of the bizarre statements coming out of his mouth right now in terms of the relationship with some of the European countries …,” Huebert said. “Does that mean a greater isolationism in the U.S.?”

On the other side of the spectrum, Bernie Sanders also seems to espouse very isolationist views, he said.

“The landscape in the U.S. of isolationism versus multilateral engagement – and I stress multilateral, not unilateral engagement – is something that I think is starting to re-emerge,” Huebert said. “And it is something that will be very troubling for Canada because we’ve always known that an isolationist United States always creates a security dilemma for us, because we depend on the U.S. but if the U.S. is basically going to withdraw, how do we then manage our security relations.”

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.