You see the salt shaker at your side, or glass of wine, while cooking but when you go to reach for it, you miss it, or knock it over.

Between visually situating it, and moving to grasp it, there are errors made in memory and then in movement. Where those errors are and how they accumulate are the subject of new research

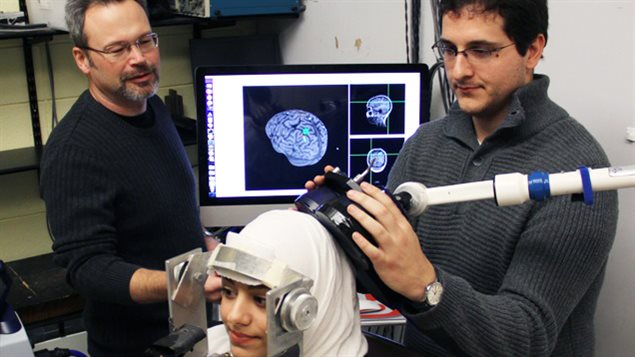

Amirsaman Sajad is a PhD candidate in the Visuomotor Neuroscience Lab at York University in Toronto, and lead author of the study.

Listen

The study was published in the science journal eNeuro for the Society of Neuroscience. The title is, Transition from Target to Gaze Coding in Primate Frontal Eye Field during Memory Delay and Memory–Motor Transformation

Using lights on a screen, subjects were shown a dot, then another off to the side which flashed only briefly. The first dot then was turned off and the eyes were tracked to where the second dot had flashed. But the subjects memory of where the dot was exactly was not particularly accurate.

The new study shows that when doing a visual task, neural activity in the frontal cortex initially reflects the visual goal accurately but then errors accumulate during a memory delay, and further escalate during the final memory-to-motor transformation. So that the gaze is directed close to where the target was, but the memory faded slightly and the transition to a movement further accentuated an error.

In other words from vision, to memory, to a physical action and how “the spatial code changes through time in the frontal cortex”.

Sajad says knowing that such errors occur in the frontal cortex can help in pharmaceutical research into better drugs to treat certain diseases related to frontal cortex function.

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.