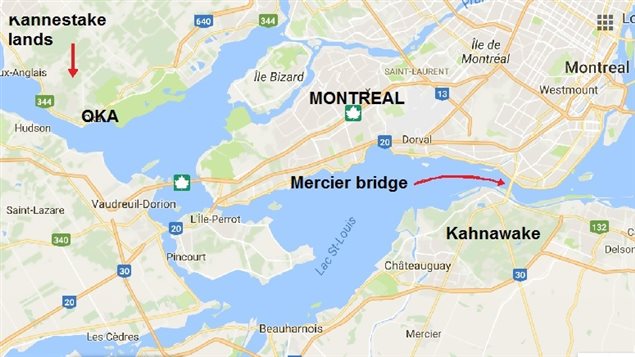

It began with argument over land between a Mohawk reserve and the small town of Oka, about 60 kilometres north-west of Montreal.

The small area of land claimed by the Mohawk reserve of Kahnestake had been in dispute for centuries. The original land grant of 1717 by the governor of New France, granted the Catholic church trustee rights to the land for the Mohawk, but the church later modified the agreement giving itself ownership of the land.

In 1868, the Mohawk demanded the land back and when that was refused, they attacked the local Catholic seminary but were forced back by military intervention.

The church sold the land to developers in 1936 and closed the seminary. Later a members-only golf course was built on a portion of the land in spite of Mohawk protests.

In 1986, a Mohawk lawsuit laying claim to the land, a wooded area known as the Pines, and burial ground was rejected by the government on technical grounds.

The situation flared however in 1989, when the mayor of the town announced permission had been given to expand the golf course and develop a residential area on the land. It should be noted that many Oka residents were opposed to this for environmental reasons, because as it was “member-only” golf club not benefitting townspeople, and because some felt it was indeed Mohawk land and knew the plan would cause tension.

In any case, the mayor did not feel it necessary to discuss with the Mohawk about the plan. In protest some Mohawk blocked road access to the area.

The tensions blew up on July 11, 1990 when the Oka mayor asked the provincial police to intervene. The Surete de Quebec (SQ) showed up with a tactical response unit, and dozens of officers. They attempted to break the blockade with tear gas and light explosive noise devices known as “flash-bangs”.

CBC-

It became a confused fiasco, and instead of chasing the Mohawk away, a shooting battle broke out between police and about 30 armed Mohawk.

To this day no-one knows who fired the first shot, but a 15 minute gunbattle ensued. The shooting left police officer Cpl Marcel Lemay dead of a gunshot wound, although it has never been made clear which side the shot came from or who the shooter was.

The police retreated leaving several police cars and a large front end loader all of which the Mohawk used to reinforce the barricade. The police set up their own barricade near town, about a kilometre away.

As a result of the attack, the group of armed Mohawk swelled quickly to about 100, and then as the standoff continued, grew to several hundred as other aboriginal members arrived from elsewhere in the country and even from the US.

In sympathy, other armed Mohawk from the Kawnewake reserve just across the river to the south of Montreal immediately blocked Montreal’s Mercier Bridge and two highways which serve many communities to the south east of Montreal such as Chateauguay. This caused huge traffic congestion and further inflamed the situation and caused bitter resentment among area non-natives. The RCMP federal force was called in but were ordered not to use force and ended up involved in riots as angry area residents demanded action to open the roads. Ten officers were injured.

Then Quebec premier Robert Bourassa requested military assistance and over 2,000 Quebec-based military personnel moved into the area.

They pushed the authorities barricade from 1.5 km from the Mohawk barricade, up to within metres. Eventually they pushed through all Mohawk barriers and surrounded the last holdout on Mohawk land.

Although there were several very tense moments and some scuffles during the weeks and months of standoff, no further gunfire was exchanged after the initial battle.

On August 29, negotiations between the army and the Mohawk on the Mercier bridge ended that blockade and thereby ending a major bargaining chip in negotiations at Oka for the group occupying “the Pines” at Oka..

On September 26, after a very tense summer standoff , the last of the Mohawk “warriors” surrendered, apparently burning some of their weapons.

The police took 26 men, and 22 women and children into custody.

In the following years, the federal government spent millions of dollars to buy land from non-natives to give a contiguous area to the Mohawk and years later bought another parcel of land so the Mohawk could expand their cemetery.

In one sense, the Mohawk did prevent development on their land. However, the members-only golf course and “Pines” are still owned by Oka, although the current mayor says no development will take place there as long as he is mayor. The forest and golf course however is still part of an ongoing land-claims negotiation involving 673 sq.km.

The 78-day Oka crisis resulted in several books written by politicians, journalists, Mohawk, and others, as well as a number of documentary films.

Additional information- sources

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.