It sounds like something from the X-Files: an abandoned top-secret nuclear weapons program, buried deep under Greenland’s ice sheet comes back to haunt humanity with its toxic contents.

But Camp Century is not a figment of Hollywood’s imagination but a very real U.S. military base crushed beneath the ice sheet and now threatening to leach its toxic contents along with melting glacial waters, according to a recently published Canadian study.

“It is an exceptionally sensational topic since it brings together climate change, the Arctic, nuclear waste, Cold War history, a bunch of threads come together in this storyline, which is why we say it is a bit of microcosm of climate change tale,” said William Colgan, assistant professor at the Lassonde School of Engineering at Toronto’s York University, and the lead author of the study.

“We see the effects of decisions made two generations ago now being played out today as we are the downstream generation having to deal with these effects.”

(click to listen to the full interview with William Colgan)

ListenThe secret beneath the ice

Designed to house 200 people, Camp Century was built in 1959 as part of a U.S. project – codenamed Iceworm – to study the possibility of deploying nuclear missiles under the ice to shield them from the Soviets, Colgan said.

He first heard of Camp Century and Project Iceworm in 2010, during a research trip to northwestern Greenland to take what’s called an “update core,” Colgan said.

“Camp Century is very special and well-known in the climate community because it’s the site of the first ice core to the bed of the Greenland ice sheet that the U.S. Army recovered back in 1967,” Colgan said. “Our job in 2010 was to back to the same site and drill from the surface to the 1967 layer to update the ice core record.”

At the Camp Century site some of the drillers told him about the mysterious military base that lay beneath the surface.

Cold War relic

Intrigued by the Cold War relic, Colgan started doing some online research and pulled out as many engineering documents as he could that described the setup of the military base.

“It was that trip to the site to take that core that piqued my interest and made me learn that Camp Century was more than just a large science project but rather is a large military project, which only had a small science project,” Colgan said.

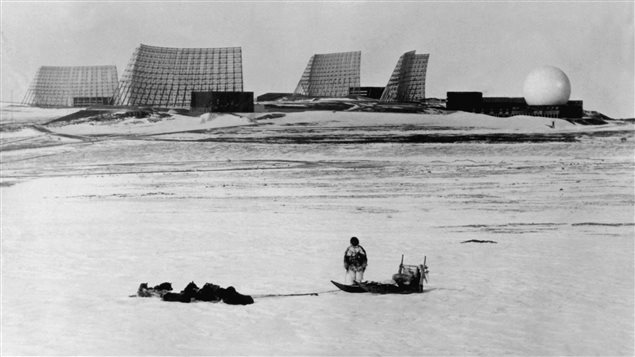

The abandoned Camp Century site, complete with a hospital, cinema, church and research labs – and powered by a mini nuclear reactor, is about 250 kilometres east of the U.S. military base in Thule, in northwest Greenland.

Camp Century was a top secret U.S. project for many years until Walter Cronkite visited with CBS and did a special called Camp Century: a City under the Ice, Colgan said.

“It was almost like a propaganda movie where the U.S. Army was broadcasting all their technological savvy in colonizing the ice sheet,” Colgan said. “It was like a little city under the ice sheet that they had dug out, just below the surface of the ice sheet.”

Ice shield for nukes

The main research project was testing the feasibility of the deployment of nuclear missiles within the ice sheet.

“They wanted to learn how to dig tunnels just beneath the ice sheet to keep missiles constantly in motion over large area of the ice sheet,” Colgan said.

The U.S. military wanted to eventually put in 600 missiles into a network of tunnels dug under the surface of the ice sheet.

“They actually went so far as building a small railway, a test railway beneath the surface and doing some other important basic research into the building materials and the structures they could construct within the tunnel walls,” Colgan said.

But all of this was abandoned in 1967, after about seven years of use.

“It was abandoned with minimal decommissioning, meaning that the doors were pretty much closed and everything was left as it was in the tunnels,” Colgan said. “They removed the nuclear reactor but other than that they left pretty much all the infrastructure in the tunnels and it was slowly crushed shut by the deforming tunnels and buried under subsequent snowfall.”

Force of nature

What remains of the base is now crushed very flat at a depth of about 30 to 35 metres beneath the ice sheet surface.

When the U.S. army engineers abandoned the site, they assumed it would snow in perpetuity, burying the abandoned site deeper and deeper in the ice sheet.

But climate change will at some point reverse that process and slowly peel off layers of ice until Camp Century is brought back to surface, Colgan said.

“When we looked at climate simulations being used by the most recent climate assessment, we found that ‘under the business as usual’ scenario one of the most reliable climate simulations suggests that the site will transition from collecting net snow fall every year to experiencing net melt,” Colgan said.

The model suggests that beginning around the year 2090 one layer of snow and ice would be removed from the site each year until its exposure on the surface is irreversible, he said.

Toxic slush

Pools of melting water on the surface of the ice sheet could exacerbate things even before the site is fully exposed, Colgan said.

“The concern with Camp Century is that the site, once it starts to receive melt, even if it doesn’t melt all the ice but rather just creates enough melt water to percolate down through the ice and through the abandoned infrastructure and the abandoned waste piles, there is the potential of dispersion of some of the pollutants that were left on that site,” Colgan said. “Those include things like PCBs and other chemicals being leached from physical infrastructure, the large volume of raw, untreated sewage left at the site, even a little bit of low-level radioactive coolant that was left at the site as well.”

A weekend project

If he can secure funding, the next step in his research is to return to the site with an ice penetrating radar and map out exactly where the site is and how deep under the surface its waste sites lie.

“Right now we only have a vague idea how deep it is based on a bit of modelling and estimation,” Colgan said.

But securing funding for this further research has been highly problematic “probably because there is some questions about how it’s a multi-generational, multi-national liability associated with the site” with no country willing to fund the project so far, Colgan said.

“It’s been an evening and weekends project by our team of junior researchers so far,” he said. “We’re hoping to get some funding and get on site within the next two years or so.”

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.