A U.S. Arctic strategy document made public this week is putting both Moscow and Ottawa on notice that Washington considers the Arctic a vital if somewhat neglected area of national security interests and intends to vigorously defend them.

“This strategy, which is the culmination of years of bipartisan effort, represents an important and necessary step forward in defining our national security interests in the Arctic and finally addressing the capabilities that the United States will need to defend them,” Senator Angus King said in a statement.

“We are an Arctic nation and with this important strategy, we are starting to act like one,” added Senator Dan Sullivan of Alaska.

The Department of Defense’s (DoD) Arctic Strategy specifically details “the ways and means DoD intends to achieve its objectives.”

‘Friction points’ with Canada and Russia

These include enhancing the capability of U.S. forces to defend the homeland and exercise sovereignty; strengthening deterrence at home and abroad; strengthening alliances and partnerships; preserving freedom of the seas in the Arctic; and evolving DoD Arctic infrastructure and capabilities consistent with changing conditions, the document says.

While the report notes that “the Arctic generally remains an area of cooperation,” it also underlines two “friction points.”

The report identifies the dual disputes the U.S. has with Ottawa over the status of the Northwest Passage and with Moscow over the Northern Sea Route, along Russia’s Arctic coastline from the Bering Strait to Kara Sea, as the two sources of tension in the Arctic.

“The most significant disagreements from the United States’ perspective are the way that Canada and Russia regulate navigation in Arctic waters claimed under their jurisdiction,” said the unclassified version of the report, which was released internally in December, almost a month before the Trump administration assumed power.

Asserting freedom of navigation?

The strategy document calls on the U.S. to conduct “Freedom of Navigation operations to challenge excessive maritime claims when and where necessary” – a direct reference to Canada’s claims to the Northwest Passage and Russia’s claims to the Northern Sea Route.

The D0D Arctic Strategy was also discussed during the meeting on Monday in Washington between Canada’s Defence Minister Harjit Sajjan and U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis, said in an email Jordan Owens, Sajjan’s spokesperson.

Global Affairs Canada is sticking to its longstanding position on the status of the Northwest Passage.

“All waters of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, including the various waterways commonly referred to as the ‘Northwest Passage,’ are internal waters of Canada by virtue of historic title,” said John Babcock, a spokesperson for Global Affairs Canada.

The U.S. Arctic Strategy has major ramifications for Canada and Russia, said Rob Huebert, an associate professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Calgary and a senior research fellow with the Centre for Military and Strategic Studies.

“It raises the very real possibility that they are going to start considering some form of freedom of navigation program,” Huebert said in a phone interview. “And freedom navigation programs are basically to challenge those countries that they think are improperly using navigational rights. And so does this mean that an American Trump administration is going to say: ‘OK, this is against American interests and therefore we’re going to push both the Russians and the Canadians on this issue.’”

Preventing diplomatic standoff

The Trump administration that doesn’t have any long-term ties or standing relationships with Canada seems quite capable of pushing Canada on the status of the Northwest Passage, Huebert said.

“If in fact this starts being American policy in light of what Trump has been doing and saying in terms of his policies for interactions with other states, I think it means that we may be facing a rockier problem than what most Canadians thought we would from the Americans,” Huebert said.

To prevent this potentially destabilizing event from taking place, Canadian diplomatic officials need to remind U.S. officials that by insisting that the Northwest Passage is an international strait, they would be opening it up to Russians and Chinese as well, Huebert said.

“It means the opening up North America’s northern flank,” Huebert said.

Longstanding U.S. policy

However, Michael Byers, Canada Research Chair in Global Politics and International Law at the University of British Columbia, said for now he doesn’t see reasons to worry too much.

“What you’re seeing in this document is continuation of 50 years of U.S. policy, which has not included challenging the Russian claims in the Northern Sea Route and challenging Canadian claims on only two occasions in 1969 and 1985,” Byers said. “I don’t see that this document is raising the stakes in any way.”

In fact since 1988, thanks to Brian Mulroney and Ronald Reagan, Canada and the U.S. have an agreement with regards to U.S. Coast Guard voyages through the Northwest Passage whereby the U.S. agrees to provide notice that they would like to conduct a voyage and Canada agrees in advance to give permission and cooperation for any such voyage, Byers said.

“That’s a situation that is very carefully and successfully managed between the two countries and I don’t see any change in that situation,” Byers said.

Obama administration document

The strategy document bears the marks of the Obama administration, Byers said.

“This is essentially the final Arctic policy statement of the Obama administration,” Byers said in a phone interview. “It contains conclusions that are informed and quite reasonable.”

The document reflects the fact that the U.S. DoD understands the reality, scope and speed of climate change in the Arctic and has incorporated climate change in all of its planning, Byers said.

Many indications point to the fact that the DoD document was intended less as a strategy document and more as an internal document looking at the U.S. strength and weaknesses in the Arctic, Huebert said.

As such it offers an insight into how Washington sees the region and its role in it, Huebert said.

“Therefore I think the fact that they’re seeing that there is a bit of a problem with the Arctic being an ‘orphaned’ and not properly supported within the overall defence family in the U.S. means that, at the very least, Americans are aware that they don’t have their Arctic security file properly coordinated,” Huebert said.

In @SASCMajority hearing, I had opportunity to ask Gen. #Mattis about #SouthChinaSea, Russian #Arctic build-up, other challenges. #SECDEF pic.twitter.com/AuCJdP21kD

— SenDanSullivan (@SenDanSullivan) January 13, 2017

‘Informed and reasonable’

However, the report is informed and reasonable with regards to security threats in the Arctic, Byers said.

“It is not in any way alarmist about Russia or China,” Byers said.

The report makes a point with regards to the fact that while Russia has certainly been scaling up its military around the world, relatively very little attention is being paid to the Russian Arctic, Byers said.

“Russia is definitely a security concern in places like Eastern Europe and the Middle East but much less of a concern in the Arctic,” Byers said.

Byers said he was critical of the map of Russian military assets presented by Senator Sullivan, arguing the Department of Defense has produced a more objective assessment of the situation in the Russian Arctic.

“Yes, they are repairing Cold War infrastructure in some cases reopening former bases,” Byers said. “But those bases relatively speaking are quite small, that infrastructure relatively speaking is fairly minor.”

Policy enigma

Both Byers and Huebert agree that the problem for Canadian policy makers is that they have no idea yet where the new Trump administration stands on many of these issues.

The Arctic Strategy document offers very little guidance on this, Byers said.

“It tells us what the U.S. Department of Defense thinks but it tells us nothing about what the White House thinks under President Trump,” Byers said.

It seems the new Trump administration is not interested in continuing Obama policies on climate change and pursuing multilateralism based on international institutions such as the Arctic Council as cornerstones of their Arctic policy, Byers said.

Silver lining

“On the positive side, in terms of the Arctic at least, it seems likely that there will be a better relationship between the United States and Russia, perhaps most notably because of the appointment of Rex Tillerson as U.S. Secretary of State,” Byers said.

Tillerson has very strong connections to the Putin government due to his involvement as head of Exxon in Russian Arctic offshore oil projects, he said.

“One can predict that tensions with Russia in the Arctic to the degree that they existed in the Arctic are unlikely to increase,” Byers said. “That’s about all we can say at the moment.”

Time to resolve Beaufort Sea dispute

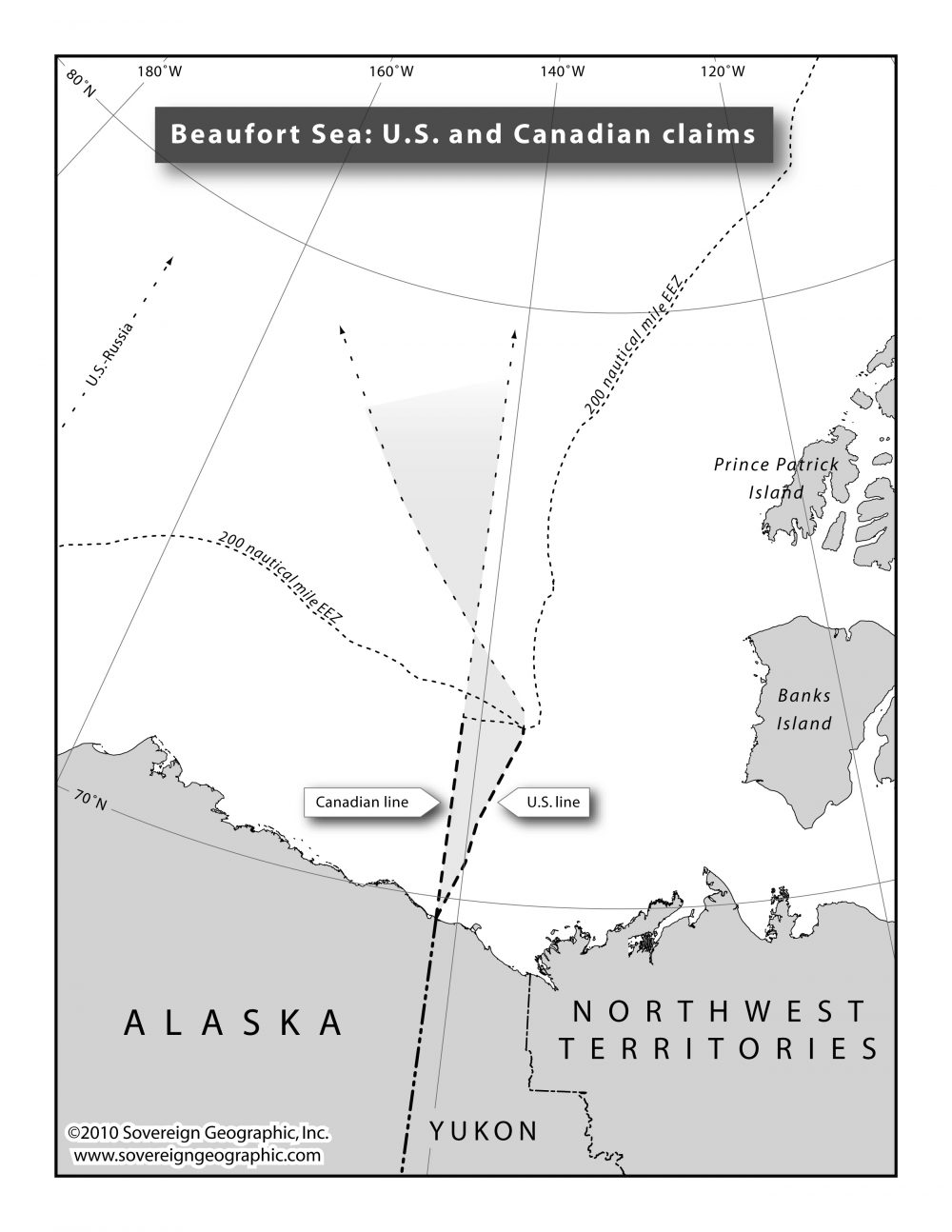

Also, little is expected to change in the near future with regards to Canada’s other Arctic dispute with the U.S. over the maritime border in the Beaufort Sea, Byers said.

“The dispute in the Beaufort Sea has always been an agreement to disagree,” Byers said. “There has been no tension whatsoever with regards to that dispute.”

Babcock said Canada favours a resolution of the maritime boundary in the Beaufort Sea.

“This dispute is well managed by Canada and the U.S. and will be peacefully resolved in accordance with international law when both parties are ready to do so,” Babcock said in an email. “Canadian and U.S. experts are engaged in a technical dialogue on the maritime boundary and on the extended continental shelf. Experts continue to be in regular contact.”

Courtesy of Michael Byers

The dispute could possibly flare up again in the future if oil prices were to jump significantly, reigniting interest in extracting offshore oil reserves off North America’s Arctic coast. But as long as oil prices remain depressed, drilling in the Beaufort Sea makes little economic sense, even if the Trump administration were to succeed in overturning President Obama’s parting executive order banning all exploration and extraction activities off Alaska’s coastline, Byers said.

In fact, now is the best time to negotiate a solution for the dispute over the maritime boundary in the Beaufort Sea, Byers said.

“One can argue that the best time to negotiate a maritime boundary dispute is when there is no significant interest in oil and gas or fisheries in the area, in other words, to resolve the dispute while the stakes are low” Byers said. “But the history of maritime boundary disputes around the world suggests that countries really only engage diplomatically when there is some kind of tension.”

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.