In the 1800’s European nations were eagerly vying for lands and possessions as they built their colonial empires around the world. Countries in Africa were among those hotly contested.

By the 1880’s, British expansion in south Africa came into conflict with that of German expansion interests, and with the Afrikaaners, Dutch farmers, or “Boers”, who were already long-established there.

Adding fuel to the situation, both the Boers and British had also been into conflict with natives such as the Zulus since the early part of the 1800’s. This led to some major battles between Zulus and British in 1879, but by 1880 the British had repulsed the Zulus, imprisoned the king and that threat was all but ended.

A first conflict between Boers and the British occurred in 1881 in which the British were essentially defeated and signed a peace treaty.

But by 1899, British colonial interests and a gold rush in the Afrikaaner’s territories once again caused conflict with the Boers whose roots in the region went back another 200 years or so. They bitterly resented British rule and of course further incursion into “their” lands ,the Orange Free State, and Transvaal.

A second war between the two erupted that year.

The Boers had initial success with their excellent marksmanship, use of camouflage and highly mobile guerilla-war tactics against the British still clinging to Napoleonic-era strategies.

Indeed the Boer word “commando” has been adopted into the lexicon of every army since, along with “laager” or a gathering of vehicles and personnel in a temporary defensive position.

First real military venture for Canada as a nation

After heavy initial losses. Britain called for volunteers from its Empire, and Canadians were among those who responded. While a substantial number of Canadians had fought in the Crimean War in the 1850’s, they were in British units. And while other Canadians had served in the Nile expedition to relieve Khartoum in the 1880’s, these were basically contracted civilians.

Thus, this expedition to southern Africa became Canada’s first organized military venture and expression of a foreign policy statement.

At first, French Canadians expressed a strong position that they did not want to get involved in a foreign war, a position that would remain during the First and Second World Wars, and cause some domestic friction and resentment between English and French speaking Canadians.

This also caused some political hesitation on the part of the federal government, but eventually the government decided to offer a battalion sized contingent of just over 1,000 men.

The new volunteer force was formed and called the 2nd (Special Service) Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry (RCRI, changed to RCR in 1901). Later, other forces of the Royal Canadian Dragoons and Lord Strathcona’s Horse would serve in the war,.

The 1,000 man force arrived in Cape Town in late 1899, and although lacking in training they were sent north towards the Modder River. There they adopted more appropriate tactics than the British style of the Napoleonic-era of standing in blocks and firing in volleys, opting instead for skirmish tactics, similar to their Afrikaaner enemy, moving forward in short rushes and firing from the prone position.

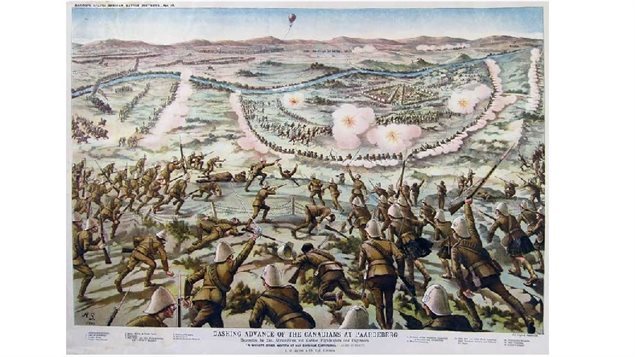

On 18 February 1900, the British forces caught up with a major Boer force near Paardeburg Drift (also spelled Paardeberg) where the Boers dug in. Initial, and poorly thought out British attacks across open ground against the entrenched Boers resulted in many casualties including several among the Canadians who had also been ordered by the British commanders to attempt another charge across the open field.

After a ten day stalemate, with British firing artillery shells and bullets into the laager, the Canadians were sent in at 2am on 27 February in a surprise attack.

Only a few dozen metres from the Boer trenches, a trip wire warned the defenders and the Canadians dug in as best they could with heavy exchange of fire. Although apparently someone called for a retreat, at least two Canadian companies continued the attack.

With all their pack animals killed by the shelling, and supplies all but gone, the Boers realized their position was untenable.

The force of over 4,000 Boer fighters surrendered to the much smaller Canadian force which had continued the fight.

The Boer surrender represented a tenth of the entire Boer force.

The Canadian action was hailed as resulting in the first major victory for the British in the war, and was a huge boost in morale for all the Commonwealth forces.

This represented the first major conflict in the first overseas venture for a Canadian force. But that would not be the end for the Canadians, The RCR would return to Canada that December, but before that they and other Canadian units were involved in several major battles throughout the spring and summer. Indeed, the Commonwealth’s highest honour for valour the Victoria Cross, would be awarded to four Canadians during the war: one to a member of the Strathcona’s Horse (later Lord Strathcona’s Horse- LdSH) and three to the Royal Canadian Dragoons (RCD). Canadians were also awarded 19 Distinguished Service Order medals,and 17 Distinguished Conduct Medals.

Eventually about 8,000 Canadians would serve in the conflict. Some 270 Canadians never returned.

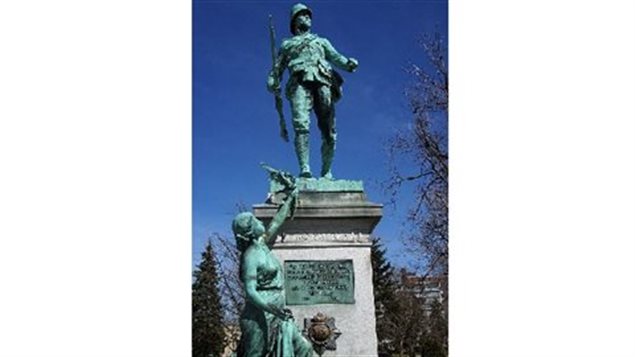

When the 2nd Battalion returned to Canada it was to a fantastic welcome, The victory added to Canadians slowly growing sense of their own nationalism and pride, as a separate and independent nation and identity. Indeed, within Canada the 27th was marked as Paardeberg Day, a tradition which continues to this day within the RCR which has Paardeberg and South Africa as battle honours, while the RCD and LdSH both have South Africa as a battle honour

Although it was a major victory, the battle did not end the war. That tragically dragged on more as a guerilla-style conflict until 1902 and as is often the case with long drawn out conflicts, it also became more vicious on both sides.

Though the British (and Commonwealth forces) were eventually victorious, there was one more word that has entered the language and that arose from that tragic war. Even at the time and ever since, it has been symbolic with great suffering as captured Boers were herded into “concentration camps” where thousands of Afrikaners died, mostly civilians, due to poor living conditions and disease.

Additional information-sources

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.