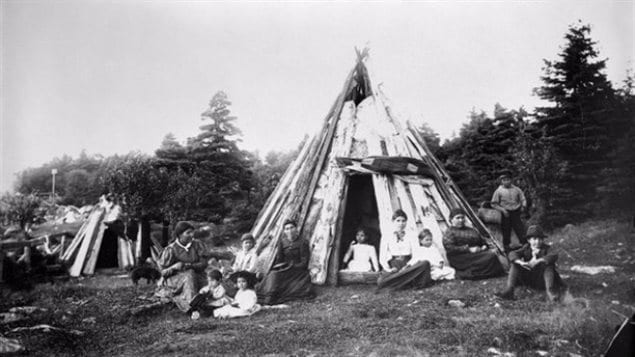

This story began thousands of years ago when a people now known as the Mi’kmaq nation, roamed much of what came to be called Eastern Canada.

They lived peacefully, working the land, hunting and fishing to survive.

Then the white men came.

Sadly, like virtually all of their indigenous brothers and sisters, members of the Mi’kmag nation were lied to, saw their land stolen, were shunted aside–disparaged and forgotten–as their European-based conquerers took control of the territory.

It’s not a pretty story, but over the last decade or so, things have begun to change both across Canada and notably in the province of Nova Scotia and its capital city, Halifax.

Universities across that province have all announced in recent months that they are making the Mi’kmaq flag a permanent part of their campuses.

Earlier this year, the Halifax Regional School Board voted unanimously to introduce a statement during morning announcements acknowledging that it’s 136 schools are on Mi’kmaq land.

The statement: “We acknowledge that we are on Mi’kamki, which is the traditional ancestral territory of the Mi’kmaq people.”

Indeed, they are.

And while in the full swath of history, flying flags and reciting statements at the start of the school day may not appear to be all that big a deal, it’s–at the very least–another step, albeit a small one, on a long and still unfinished road toward rectifying and recognizing past wrongs.

Patricia Doyle-Bedwell is an associate professor of aboriginal studies at Dalhousie University in Halifax, one of the Nova Scotia schools attempting to make amends.

She is also a mother, a lawyer, a writer, an historian and a social activist.

And she is a Mi’kmaq.

I spoke to her by phone Wednesday at her office in Halifax about the recent changes and the conditions from which they arose.

Listen

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.