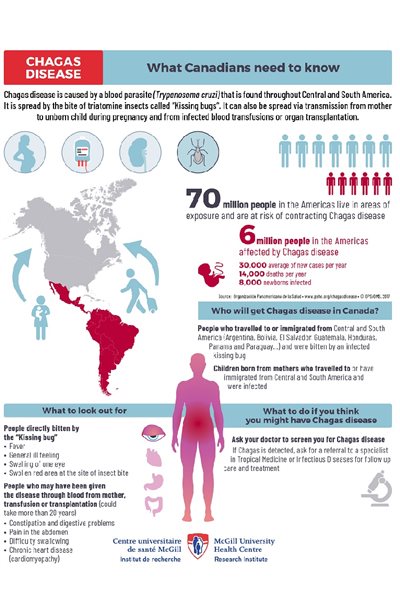

With world travel so easily available, and through immigration, there are very few diseases now that are limited to one geographical area of the world.

This is the case with “chagas” disease.

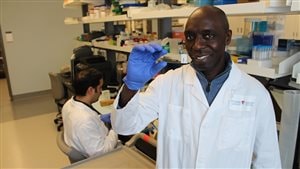

Momar Ndao (PhD, DVM) is a scientist from the Infectious Diseases and Immunity in Global Health Program at the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre (RI-MUHC), and an associate professor in the Department of Medicine at McGill University

ListenR

esearchers in Canada have discovered some new concerns about the disease which is occurring mostly in Latin America. They found it can be more common than thought in immigrants and even in children who have never been to their parents country of origin or seldom returned to those areas

They found for example that Chagas disease can be transmitted through the womb.

The research was published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ) under the title, Congenitally transmitted Chagas disease in Canada: a family cluster”. Dr. Pierre Plourde, Medical Officer of Health and Medical Director of Travel Health and Tropical Medicine Services with the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority (WRHA), was the study’s corresponding author.

The research involved scientists from Montreal and Winnipeg into what is known as the “kissing bug” disease, so-called because the blood sucking insect tends to bite the face of its victims. The parasite causing the disease is released through the bug’s faeces. The protozoan parasite can enter the body through the bite of other open wound.

The initial symptoms are flu-like in nature, but can fade and seem relatively dormant for two or three decades.. The parasite can eventually infect other areas of the body like the intestines, and heart, eventually leading to a premature death.

However, many people can have the disease in its dormant stage and not know about it. During that time the disease can be transmitted to others through blood donations, or organ transplants.

In the course of their research the scientists discovered the case of a man who had donated blood several times until it was discovered in 201- that he carried chagas.

While blood donations are now screened for the disease in Canada, professor Ndao says anyone who travels to Latin America who may have been bitten by an insect should ask for testing.

According to the authors, the countries known to pose the highest risk for contracting Chagas includes Argentina, Bolivia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Panama, and Paraguay.

Because the Canadian research has revealed the disease can be passed to children through the womb, any child of immigrants from Latin America born in Canada, or other countries outside endemic areas, should also ask to be tested.

Indeed, he suggests that anyone travelling to an endemic country, as well as all immigrants, including children, should be tested upon entry.

He notes that the disease can be treated easily in its early “acute” phase, but it is much harder to treat afterward, and even after th 60-day treatment, cure may not be complete.

Ndao says they are now working on a bio-marker detection to be able to determine when the disease has been completely eliminated in a person.

Dr Plourde worked in partnership with parasitic diseases laboratory specialists Dr. Kamran Kadkhoda, Clinical Microbiologist from Cadham Provincial Laboratory in Winnipeg, and Dr. Ndao, head of the National Reference Centre for Parasitology (NRCP) at the RI-MUHC.

(with files from Julie Robert RI-MUHC)

Additional information –

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.