As dozens of Inuit leaders from Greenland, Canada, the United States and Russia gather in Alaska this week, they will look at strategies to get a greater voice for the Arctic Indigenous group in international and local governance, says Canadian Inuit leader Nancy Karetak-Lindell.

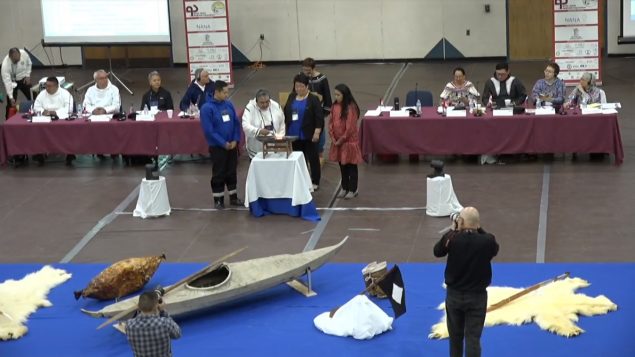

Sixty-six Inuit delegates from Canada, Alaska, Greenland and Russia’s Chukotka region will be meeting in Utqiagvik (formerly known as Barrow) from July 16 to 19, 2018 for the Inuit Circumpolar Council’s (ICC) 13th General Assembly, whose theme this year is “Inuit – The Arctic We Want”.

The ICC represents an estimated 160,000 Inuit living in Greenland, northern Canada, Alaska and Chukotka, an area that covers more than 5 million square kilometres.

The delegates are expected to discuss policies and strategies that will guide the work of ICC for the upcoming 2018-2022 term, under the Alaskan Chairmanship.

During the four-day meeting, the delegates will discuss a draft of a declaration that comes out every four years during every assembly, said Karetak-Lindell, outgoing president of ICC Canada.

Insisting on Indigenous rights

“Overall it’s about including Inuit in all the decision-making that happens around us and above us and somehow doesn’t take our Indigenous rights into consideration,” Karetak-Lindell said in a phone interview from Utqiagvik.

“We have to be very vigilant in making sure that we, the people that live in these communities that are affected by development, (maritime) traffic, by the environmental changes, political changes, we want to be part of the decision-making process.”

People have to recognize that the Inuit have Indigenous rights that give them the authority to insist that they sit at the table and be part of the decision-making process, Karetak-Lindell said.

“Whatever decisions are made around the world, they affect us and our communities, our families, our children, our environment, our wellbeing, our health and our food,” Karetak-Lindell said. “So it is only right that we be part of the decision-making process.”

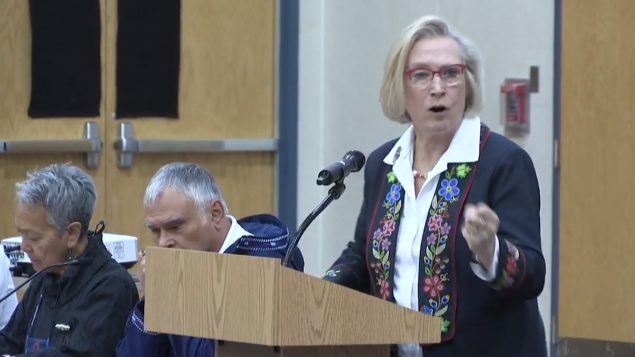

Carolyn Bennett, Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs, addresses the Inuit Circumpolar Council’s 13th General Assembly. (ICC/Youtube)

In 1983, the ICC was granted consultative status at the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) of the United Nations.

The ICC is working to get permanent representation at various other UN bodies, including the International Maritime Organization, the UN specialized agency that regulates international maritime shipping.

In 1996, the ICC played an integral role in creating the Arctic Council, which consists of eight Arctic states and six Permanent Participants, including the ICC.

However, there are things to do closer to home, Karetak-Lindell said.

“We are in our countries trying to make sure our governments respect the (UN) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and it’s up to us in our respective countries to keep at our governments to respect that international declaration,” Karetak-Lindell said.

“In Canada our government finally accepted it but we have to be vigilant and make sure that all departments when they are making decisions – whether it’s fisheries, transportation, health – that they keep that in mind as people who are writing legislation, lawyers, advisers, policy-makers are constantly aware that we have these rights that have to be taken into consideration.”

The days of southern paternalism are over, Canada’s Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Carolyn Bennett told participants of the assembly in her address.

“It is only when the Arctic policy led by Arctic people and focused on the wellbeing and the prosperity of your people that we will actually get this right,” Bennett said. “As Canadians we know that it has to represent the priorities of people living there. And the conversations about the north must be led by people of the north.”

Respecting Indigenous knowledge

Another critical area for the ICC is ensuring the respect of the traditional Inuit knowledge in the decision- and policy-making process, Karetak-Lindell said.

“We wouldn’t have survived in areas that we live in if we didn’t know how to survive with incredible knowledge,” she said. “And that sometimes doesn’t get respected, especially by science. It’s getting better but we want it to be respected in the same level as Western science, if not more in certain areas.”

Canada has invested in two programs that help harness the traditional knowledge of Inuit and other northerners on climate change policy, Bennett said.

Ottawa has invested $25 million to support Indigenous orginazations participating in the development of domestic climate change policy and more than $83 million will help integrate traditional knowledge into community-based climate monitoring and climate change adaption, Bennett told participants of the ICC assembly.

Respecting Inuit governance systems

One of the biggest examples of disregard for the traditional Inuit knowledge is the eradication of traditional Inuit governance models, Karetak-Lindell said.

“We had our own system of governing ourselves until someone came and decided we didn’t have any and had to impose one on us,” Karetak-Lindell said.

“We have people that are suffering now because no one took into consideration how we made sure that we kept our people healthy.”

Taking away leadership from people who were recognized to be leaders in their community and giving it to people who were not fit for the job eroded the Inuit social structure and led to the current crisis, she said.

Despite the challenges faced by the Inuit over the last 100 or 50 years, they have survived, Karetak-Lindell said.

“Time is against us and the longer we don’t take matters into our own hands, the more knowledge we lose from our elders that are passing away,” she said.

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.