The federal government and Dehcho First Nations in the Northwest Territories have agreed to a landmark deal that will protect a “breadbasket” wilderness area from resource development for generations to come.

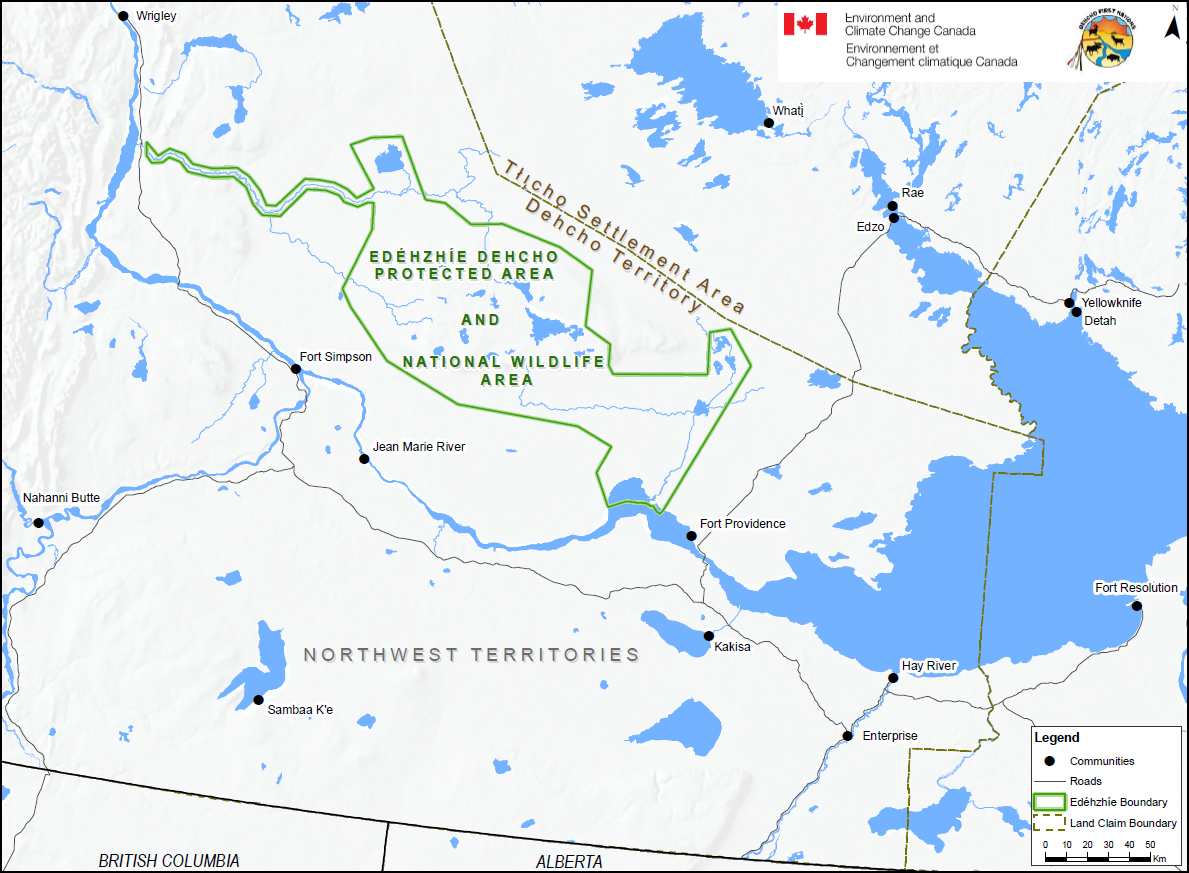

The agreement signed by Environment Minister Catherine McKenna and Dehcho First Nations leaders in Fort Providence, N.W.T., on Thursday protects from any future development more than half of the Edéhzhíe area, a plateau that rises out of the Mackenzie Valley to the west of Great Slave Lake.

The Edéhzhíe Indigenous Protected Area/National Wildlife Area will conserve 14,249 square kilometres of boreal forest and will be jointly managed by Dehcho First Nations and the federal government.

“Our government has made a historic investment in protecting nature from coast to coast to coast,” McKenna said. “By creating the Edéhzhíe Dehcho Protected Area and National Wildlife Area under the leadership of the Dehcho First Nations, we are protecting a very special place in Canada while working in partnership with Indigenous peoples to advance reconciliation.”

Dehcho K’éhodi Indigenous Guardians and the Canadian Wildlife Service will draw on Dene culture and traditional knowledge and western science to carry out on-the ground monitoring and protection activities.

The agreement will promote and encourage the Dehcho Dene way of life in Edéhzhíe, said Dahti Tsetso, resource manager and director of the Dehcho K’éhodi Stewardship and Guardians program that will manage the new protected area.

“My generation, we consider ourselves intergenerational survivors of the residential school impacts,” Tsetso said in a phone interview from Fort Simpson, N.W.T. “And so working actively towards initiatives that help us reconnect with our culture, to our elders and to our language and to the land are such an integral part of our self-identity process on an individual level and then part of a healing process on a wider community and regional level.”

(listen to the full interview with Dahti Tsetso)

ListenDehcho breadbasket

Edéhzhíe is home to headwater lakes, mature spruce forests, and vibrant wetlands; this diversity supports 36 mammal species, 197 bird species and 24 species of fish. (Bill Carpenter/Dehcho First Nations)

The area holds great significance for Dehcho culture and identity, she said.

It includes many important spiritual sites and figures prominently in Dene stories.

“It’s been used, our elders say, since time immemorial to harvest fish and wildlife,” Tsetso said. “During times of scarcity they could always relay on Edéhzhíe to provide them with sustenance.”

Dene elders refer to Edéhzhíe as the breadbasket of the Dehcho, because of its natural bounty, Tsetso said.

Edéhzhíe is home to headwater lakes, mature boreal forests and vibrant wetlands that support 36 mammal species, 197 bird species and 24 species of fish.

Boreal caribou and wood bison – both species at risk – roam in its spruce forests, which are also home to populations of many bird species recognized as nationally threatened or of special concern, including Canada warbler, olive-sided flycatcher, rusty blackbird, common nighthawk, and short-eared owl.

The Edéhzhíe area is also very important for their Tłı̨chǫ neighbours, Tsetso said.

A 20-year process

Source: Government of Canada

The agreement, which comes after 20 years of negotiations with Ottawa, sets out mechanisms of the area’s co-management with the federal government as well as a dispute resolution mechanism, Tsetso said.

“We’ve had 20 years to really think it over, 20 years to figure out what areas are important and how we approach management,” she said.

In July, Dehcho leaders designated Edéhzhíe as a Dehcho Protected Area under Dehcho Dene law and the agreement with the federal government means that it will also get federal protection, Tsetso said.

“In order to achieve this sort of protection for lands it takes patience, it takes dedication and commitment, and it also takes willingness to listen to one another, to compromise and to find a pathway towards consensus,” Tsetso said.

A part of the tough discussions was finding an appropriate balance between conservation and development, she said.

The new boundary, which protects the lion’s share of the Edéhzhíe area but leaves others open to development, represents that compromise, she said.

Trailblazing work for Indigenous communities across Canada

Valerie Courtois, director of the Indigenous Leadership Initiative, an Indigenous NGO that works on strengthening Indigenous leadership and is a partner in the International Boreal Conservation Campaign, said the Edéhzhíe agreement is a “representation of the possible” for the rest of Indigenous Canada.

“Edéhzhíe really is a representation of the work that’s being done by Indigenous Peoples right across Canada in really looking at what sort of future do they want for their land and in that conversation determining what needs to stay in order for those lands to be healthy,” Courtois said in a phone interview from Happy Valley-Goose Bay, in Labrador.

(listen to the full interview with Valerie Courtois)

ListenIt also brings the government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau a step closer in its goal of protecting at least 17 per cent of Canada’s lands and inland waters by 2020 as part of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity.

Edéhzhíe is the first Indigenous protected area established since Canada launched the Pathway to Target 1 process to achieve the goal and committed $1.3 billion in the 2018 federal budget to support collaborative conservation efforts, Courtois said.

“Our hope is that it inspires Indigenous nations of Canada to think about how they can contribute towards this national target,” Courtois said.

“And many already are. We have a number of partners that span from Newfoundland and Labrador right through to Yukon, who are all working to really think about the future of their lands and in doing so tend to have much bolder, more innovative approach to conservation.”

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.