“Young people are drowning in a rising tide of perfectionism,” say Canadian researchers Simon Sherry of Dalhousie University and Martin Smith of York St John University. They and colleagues have conducted one of the largest studies on the condition and have found perfectionism has increased substantially over the past 25 years and that it affects men and women equally. They also found perfectionists become more neurotic and less conscientious over time.

‘Perfectionism can be dangerous’

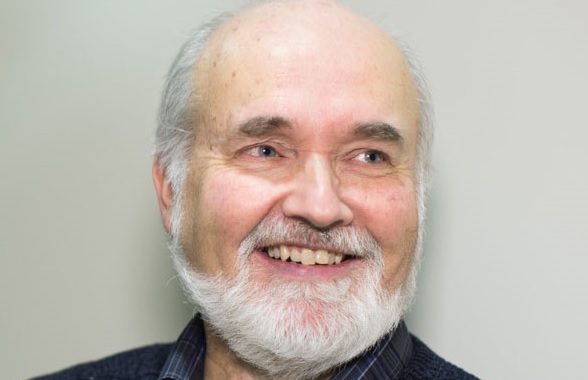

“Perfectionism is striving for extreme standards from an all or none perspective,” says Gordon Flett, a professor of psychology and a director of research at York University in Toronto. “The person who is a perfectionist wants to be absolutely perfect. Falling even short by a little is extremely frustrating for them…They’re always working in a way that can be quite exhausting.”

Perfectionism can also be dangerous, say researchers. It is linked to anxiety, stress, depression, eating disorders and suicide.

Young people may be bombarded with ‘unobtainable standards of perfection’ online, say researchers. (iStock)

Perfectionism called ‘a major, deadly epidemic’

Among the causes, researchers list “today’s dog-eat-dog world, where rank and performance count excessively and winning and self-interest are emphasized.” Social media show images of lives that are unrealistically perfect “depicting unobtainable standards of perfection.”

Researchers also mention “controlling and critical parents also hove too close in raising their children, which fosters perfectionism’s development.”

As perfectionists get older they may become more prone to guilt, envy and anxiety and they may dwell on their imperfections and become less likely to pursue their goals. They may burn out.

The researchers call perfectionism “a major, deadly epidemic in modern western societies that is seriously under-recognized.”

Prof. Gordon Flett describes perfectionism, its causes, prevention and treatment strategies.

ListenAwareness, resilience can help

The first step in tackling the problem, sats Flett, is to raise awareness about it and then to work on preventative efforts with parents, teachers and communities. Perfectionists don’t cope well when things go wrong and, as happens often in life, things are not perfect. Flett says, they can be helped. “We can certainly teach ways to be resilient. We can talk about modelling calmer reactions when there are failures and setbacks. We also promote…the idea that failure and mistakes are learning opportunities. They’re not flaws and defects.”

Flett says there is a great benefit too in telling the stories of famous people who have struggled and not been immediately successful to show that there are challenges and ways to overcome them.

“We want to replace the self-critical reactions that perfectionists tend to have by teaching them how to be more self-accepting and to develop a sense of self-compassion, self forgiveness and then extending that compassion and forgiveness to other people if they are expecting them to be perfect as well.”

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.