The New Raw – Contemporary Inuit art

CAPE DORSET (KINNGAIT), Nunavut – Ask Inuk artist Ningeokuluk Teevee if global warming has affected her community and, if you watch close enough, you’ll see her hands shake ever so slightly.

“I know it did when two young men lost their lives, because where there used to be ice…”, Teevee pauses, closes her eyes, and takes a deep breath before continuing. “They lost their lives going through the ice.

“Early ice melting means less time out on the land fishing, so it’s affected our lives. It’s just everyday life now, but it’s very, sometimes scary. I worry about what if we don’t get much food from the sea anymore or from the land? The cost of living up here is very high.”

Teevee is primarily known for her work depicting Inuit legends and wildlife. But it wasn’t long before themes like the environment, pollution, drugs and alcohol, began making their way into her work, she says.

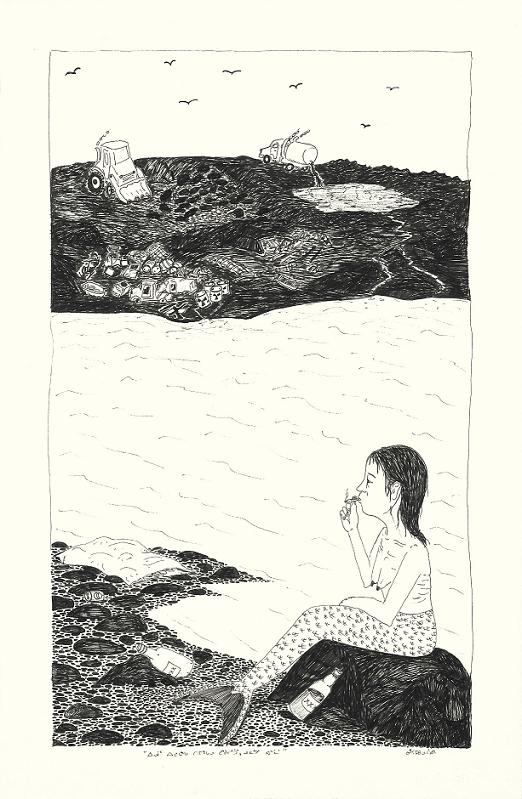

Her expression gets serious when she describes Sedna by the Sea, her ink drawing depicting the Inuit goddess smoking a cigarette and surrounded by pollution and empty bottles of booze.

And then there was the drawing she did of a polar bear swimming towards a Coca-Cola bottle.

“I was in Ottawa with my son and I saw a Coca-Cola bear,” she says referring to mascot used for the company’s campaign to raise awareness about climate change and its affect on the world’s polar bear population. “But we see Coca-Cola cans floating around,” she says motioning in the direction of the sea, “so that’s something.”

“I think I called it The Irony. ”

Politics, environment and identity

Global warming is having a profound effect on the circumpolar world. Late ice formation and early melt are changing animal behaviour and ancestral travel routes long-used by Inuit. These disruptions to traditional hunting patterns are stressing the social fabric in many Inuit communities – places already grappling with problems from substance abuse to suicide.

Inuit artists like Teevee, Jutai Toonoo and Kavavaow Mannomee, among others, are increasingly taking on these political, environmental and identity questions in their work.

But while a contemporary artist working in Vancouver, Toronto or Montreal would be praised, debated and celebrated as a provocateur for tackling these issues, Inuit artists working with the same themes are often ignored by the contemporary art world and visual arts market in the South.

And according to some experts, the public has no idea what it’s missing out on.

The beginnings of an art phenomenon

In the 1900s, the Canadian government actively encouraged carving and art production among indigenous people in Canada’s Far North. The government hoped it would encourage economic self-sufficiency among Inuit who were being transitioned out of their traditional semi-nomadic hunting and gathering lifestyle and settled into permanent communities.

In the 1950s, Canadian artist James Houston moved to Cape Dorset, an island community off the southwest coast of Baffin Island. There, he taught local Inuit how to draw and make prints. Starting in 1959, the prints produced in Cape Dorset were released in an annual collection. Though carvings produced throughout the North remained hugely popular, the Cape Dorset prints of Arctic nature and traditional Inuit life became a hit in the art world and a favourite of collectors.

The collection’s success inspired other northern communities like Ulukhaktok (Holman), Northwest Territories; Baker Lake, Nunavut; and Puvirnituq, Quebec to set up similar arts studios or centers.

Inuit art was now officially on the map.

Climate and social change alter notions of Inuit art

But there’s arguably a downside to all this. The marketing of traditional Inuit carvings and imagery to the South has been so successful, ‘Inuit art’, in the minds of most people, has become synonymous with depictions of a romanticized past in Canada’s pristine North.

Fifty years after her work first appeared in the Cape Dorset print collection, artist Kenojuak Ashevak remains a Canadian superstar for her imagery of Arctic nature and wildlife. Her work has been replicated on everything from Canadian stamps to stained glass windows.

But for Northern artists exploring contemporary themes, that kind of success is almost unimaginable.

Even after the success of Inuit artist Annie Pootoogook, whose images of contemporary family life in the North helped nab her the 2006 Sobey Art Award, one of Canada’s most prestigious art prizes, the contemporary market in southern Canada has been slow to accept new imagery coming out of the North.

That’s left many Inuit artists stranded between a southern art market that clamors for depictions of an idealized Inuit lifestyle that no longer exists and a contemporary art world that they’re often excluded from.

“The reasons are manifold from the social to the historical to the geographical,” says Leah Sandals, a Toronto-based art critic for Canada’s National Post newspaper and associate online editor for Canadian Art, one of Canada’s most prominent visual arts magazines.

“But likely none of the reasons are fair. As a result, Inuit art is generally marked, exhibited and distributed apart from the contemporary Canadian art scene – a sphere that’s often focused on a few select themes, centres, styles and courses of training.”

Robert Kardosh, curator of the Marion Scott Gallery in Vancouver, British Columbia, regularly organizes exhibitions by Inuit artists who explore contemporary themes. But he says it’s a challenge just to get contemporary art journals and critics out to the exhibitions.

“I’m not sure if it’s prejudice,” Kardosh says. “But as long as Inuit art is treated as ‘not real art’ or as simply ethnological art, people are missing out.

“The classic Inuit art of the past is spectacular and should absolutely be treasured. But art changes. It’s silly to think that for some reason, Inuit art shouldn’t.”

Inside Kinngait Studios

Cape Dorset, known as Kinngait in the local language, is a predominantly Inuit community of approximately 1200. The print program started by Houston over 50 years ago is still going strong. Kinngait Studios, where the print and drawing programs are now housed, is where many of the biggest names in Inuit art continue to work.

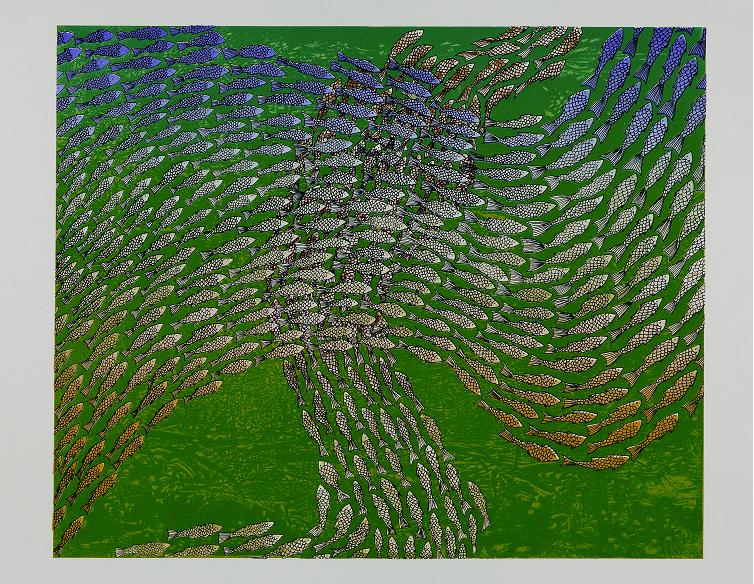

On this particular winter morning, Shuvinai Ashoona is the first artist to arrive. She heads directly for a large drawing table in one of the back rooms. She crawls up on a stool and folds her legs beneath her. Leaning over, she sprawls over the large-scale, almost psychedelic-looking drawing in front of her. She presses her face close to the paper and makes stroke after colourful stroke.

“I’m doing a banana lady (riding in) an amauti from the salt water,” Ashoona tells a visitor matter-of-factly, using the Inuktitut word for the kind of parka Inuit use to carry their babies in.

“And (the amauti) is also carrying a clam from the beach… ” Ashoona goes on to describe each aspect of the fantasy world she’s created on paper.

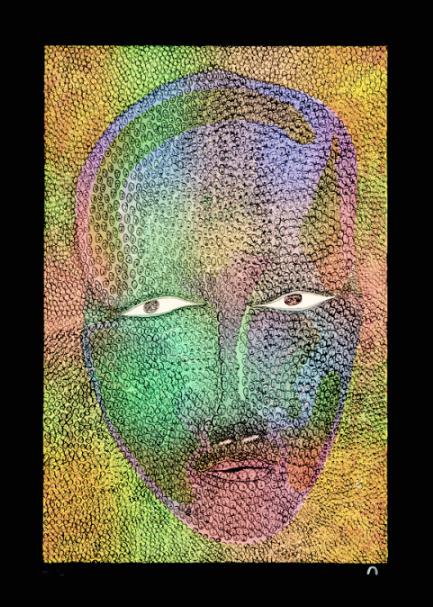

Later, Jutai Toonoo arrives wearing a t-shirt emblazoned with a Montreal Canadiens hockey team logo. Toonoo is known for carvings and drawings that explore everything from identity and emotional turmoil to culture and religion in the Arctic.

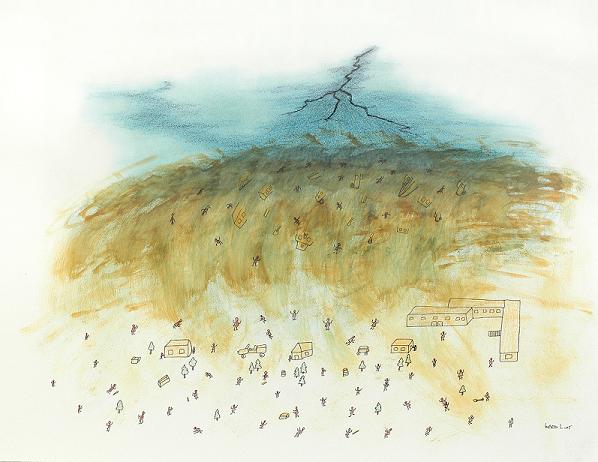

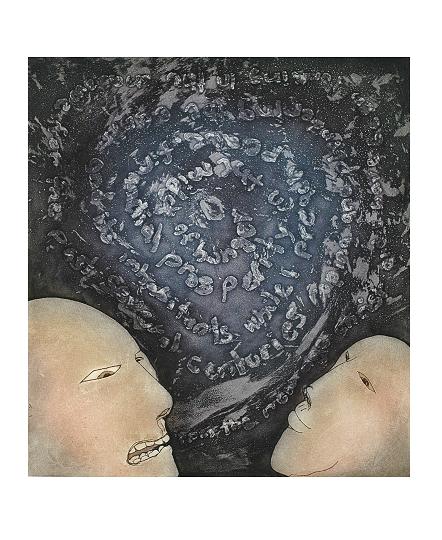

Gently, he spreads one of his works on a nearby table. It’s an unfinished drawing depicting hundreds of miniature stickmen that look like they’re walking, or maybe dancing, inside two tortured faces.

Toonoo stares quietly at the drawing before wiping his palms with blue chalk and hoisting his large frame up on the table. Now almost lying on it, he starts wiping his chalky palms into the drawing, wriggling and squirming so he can reach the far corners of it. When he’s finished, the drawing’s entire background is covered in soft blue and sweat is dripping from his forehead.

“Maybe Man and Wife,” he says looking at the image and considering the title.

Still working on the drawing, Toonoo says he wouldn’t think of changing his art to make it more palatable to southern dealers and collectors.

“Even though some of the carvers are stuck with doing polar bears and inukshuks, I try not to do that,” Toonoo says. “And sometimes I suffer for it, because right now only the co-op will buy my work.

“I think they see something that other people don’t see.”

Bill Ritchie, the Newfoundland artist who now manages Kinngait Studios, says the art produced by people like Ashoona and Toonoo is typical for Kinngait Studios these days. Ritchie opens drawers of archived artwork and excitedly pulls out drawing after drawing depicting everything from social breakdown to environmental politics to sexuality.

The public will probably never see any of it, he says.

“People in the south still think Inuit live in igloos, they run around in dog teams,” Ritchie says later on. ” I don’t have a problem here getting artists to work with contemporary issues. Their realities here are their realities and I just encourage them to do what they know.”

The frustration comes, he says, with getting that art seen, discussed and sold in the south.

“I think it’s going to be curators, it’s going to be intelligent retailers that are going to reach out and find people that once loved Inuit art for its newness and its rawness, to have a new look, to see the new raw, and the new thought, that’s coming out of the Arctic.”

Redefining Inuit art

Nancy Campbell, an independent art curator, is one of a handful of Canadians working to change the perception of Inuit art. Her two recent exhibitions, Scream and Noise Ghost, both held at the Justina M. Barnicke Gallery in Toronto, featured contemporary Inuit artwork side-by-side with contemporary artwork from southern Canada.

“I walk a very fine line in what I do,” Campbell says. “My curating work often isn’t ‘contemporary’ enough for the contemporary market and it’s not ‘Inuit’ enough for the collectors of the traditional Inuit art.

“I think that both collectors of traditional Inuit art and contemporary art critics, have preconceived notions about the Arctic. Most of them have never been there so they haven’t seen first hand both how beautiful and how tragic it is. It’s both aspects that make the North so fascinating but I think a lot of people still don’t want to see both sides.”

But as issues like Arctic sovereignty and global temperature change increasingly push Northern issues onto newscasts and into headlines – some think the southern arts community is slowly waking up to contemporary work from the Arctic.

Wayne Baerwaldt, director and curator of the Illingworth Kerr Gallery at the Alberta College of Art and Design and the former director of Toronto’s renowned Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery, was on the jury that eventually awarded the 2006 Sobey Art Award to contemporary Inuit artist Annie Pootoogook.

“There were so many people on the jury at that time who were resistant to Annie winning,” he remembers. “They said because she was from the North that she wasn’t ‘informed’ enough, hadn’t been exposed to modernism and hadn’t had formal training at art college like other artists did. For me, that was like listening to some 19th century discourse.

“I think there was also this long-standing perception that, because of its history, that ‘Inuit art’ is a commercial form of cultural production and therefore ‘artificial’ while contemporary art from the south comes purely from the spirit of the artist and is therefore ‘authentic.’ But who can say what motivates any individual artist, no matter where they come from?”

For more than just the art world

The high cost of travel to the North means few Canadians will ever see day-to-day life in the Arctic first hand. Contemporary visual arts may be among the most important cultural records we’ll have of how rapid environmental and social change is altering the North, some experts say.

“It is vital that we, as audiences, embrace and encourage new Inuit art that explores contemporary issues,” says Norman Vorano, curator of Contemporary Inuit Art at the Canadian Museum of Civilization in Gatineau, Quebec. “Most importantly because Inuit have important perspectives on issues that concern us all like environmental change, society, treatment of elders and even things like business. The list could go on and on…”

“Appreciating modern Inuit art helps us move beyond the old colonial lens, when Inuit were seen as belonging to a distant past, living outside the present,” he says. “Acknowledging the vitality, relevance and importance of modern Inuit art is also a tacit acknowledgment that both Inuit and non-Inuit live in a shared world, experiencing a shared present, occupying a shared globe.”

But until that day, Inuit artists like Jutai Toonoo say they’ll just keep on doing, what they’re doing.

“I don’t really care about the art world,” Toonoo says, more concerned with working on his drawing than considering where his work may one day fall in the Canadian art canon.

“This is just something I do,” he says, adding colour to the paper with small careful strokes.

“Lots of times it’s just something I’ve observed in the community or the world and I just put it on whatever I’m working on.

” Put it out there just so that it’s showing.

“And not hidden.”

Write to Eilís Quinn at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca