Canada’s ice road to diamonds

SOMBA K’E/YELLOWKNIFE – A late March blizzard has finished blowing over much of Canada’s Northwest Territories and Ron Near’s job just got more interesting.

SOMBA K’E/YELLOWKNIFE – A late March blizzard has finished blowing over much of Canada’s Northwest Territories and Ron Near’s job just got more interesting.

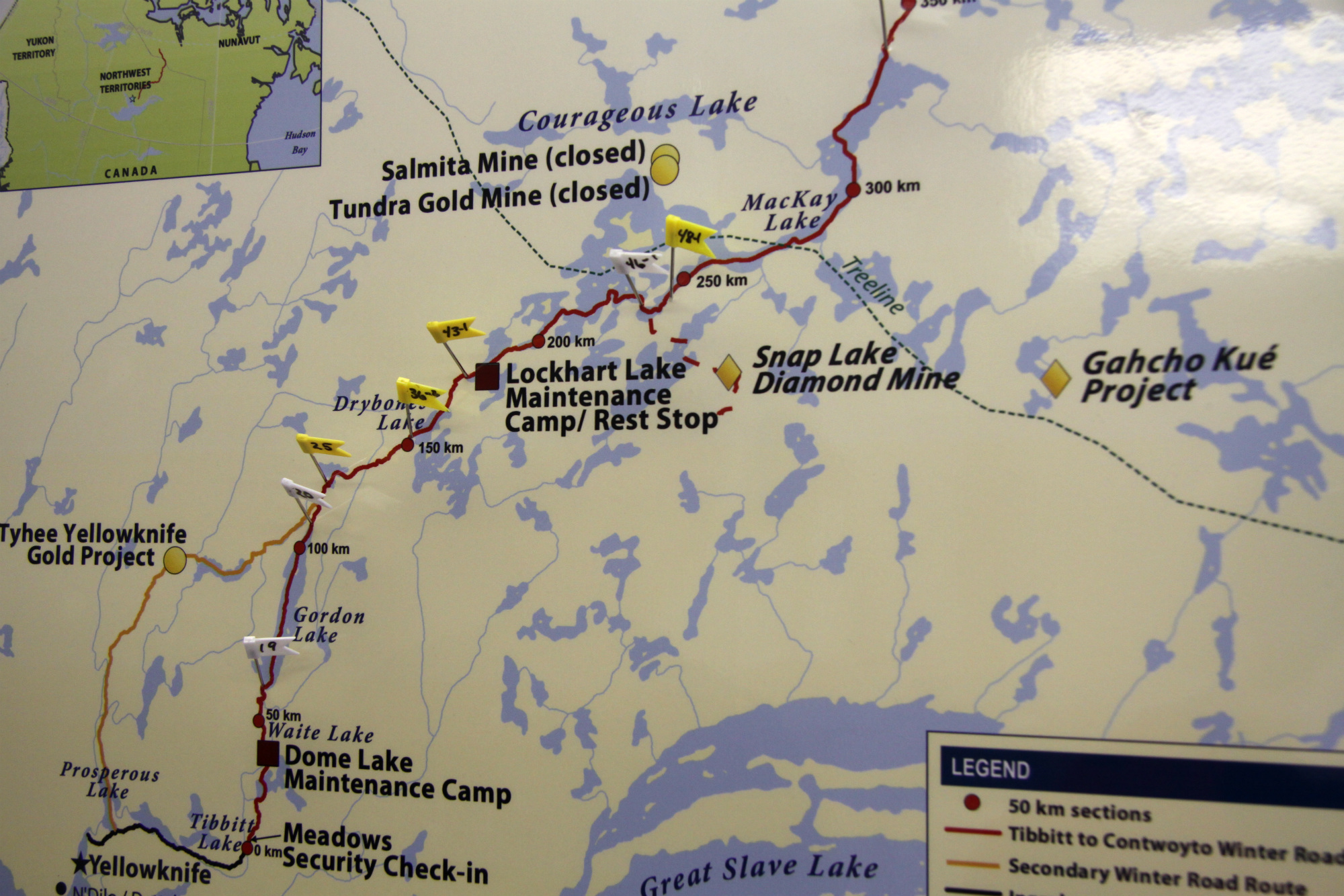

A retired Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer, Near is in charge of the world’s longest ice road that connects Yellowknife, the territorial capital, to three diamond mines: Ekati, Diavik and Snap Lake.

The Tibbit to Contwoyto Winter Road – named after the first and the last lakes on the ice road – is a joint venture between BHP Billiton, which owns the Ekati Mine, the Diavik Diamond Mines Inc., which manages the Diavik mine, and DeBeers, which owns the Snap Lake Mine.

|

Links to our series on diamond mining in the Northwest Territories: Canada – a diamond mining superpower Diamonds fuel the Northwest Territories’ economy Diamonds – the darker side of prosperity Social ills keep many on the sidelines of NWT’s diamond boom |

The ice road is the only overland resupply route for the mines. They depend on it to truck in a year’s worth of supplies and equipment: everything from diesel fuel and ammonium nitrate for mine explosives to earth moving machines.

And with the ice road open only eight to 10 weeks every year, resupplying the mines is a monumental logistical undertaking executed with military precision.

But on this particular day the entire Tibbit to Contwoyto winter road is snowed in and the window of opportunity to move tens of thousands of tons of materiel and supplies just got a whole lot narrower.

“We have 98 trucks at Lockhart Camp, which is about half-way up the winter road, that’s our main rest stop,” Near said pointing the location of the camp on a large map hanging on the wall of his office.

“We have 98 trucks at Lockhart Camp, which is about half-way up the winter road, that’s our main rest stop,” Near said pointing the location of the camp on a large map hanging on the wall of his office.

The camp has hot meal facilities, washers and dryers for the drivers, showers – anything that the drivers might get at a conventional truck stop anywhere else in North America, except this one is located right in the middle of the Arctic wilderness, almost at the edge of the treeline.

“When we see a storm starting to develop, we’ll track it,” Near said. “And once it looks like it’s going to get bad we start funnelling trucks into the different camps.”

Now he has to figure out how to get everything moving again and make up precious time the winter storm stole from them.

‘The longest school zone in the world’

The ice road begins at Tibbitt Lake at the end of the narrow and winding Ingram Trail, about 60 kilometres (36 miles) east of Yellowknife. From there, it snakes up north over frozen lakes and short overland stretches, called portages. These days it goes only as far north as the Ekati mine. But up until 2008 the ice road used to go to the now closed Jericho diamond mine on Contwoyto Lake, in south-western Nunavut.

With most of it laid over lake ice, the road must be rebuilt each year, Near said. Construction usually starts shortly after Christmas each year. And it takes five to six weeks to have the road ready by the last week in January, he said.

During construction, special amphibious tracked vehicles, Hagglunds, measure the ice thickness every day, Near said. Construction crews clear the snow and drill holes in the ice to flood certain areas and build up ice thickness to a point when it can take the weight of a fully loaded freighter truck.

During construction, special amphibious tracked vehicles, Hagglunds, measure the ice thickness every day, Near said. Construction crews clear the snow and drill holes in the ice to flood certain areas and build up ice thickness to a point when it can take the weight of a fully loaded freighter truck.

When the ice reaches 107 cms (42 inches) along the entire 400-kilometre road, it is thick enough for a super B tanker, hauling two tanks of fuel weighing approximately 41-42 tonnes in total, Near said.

Fully loaded trucks are allowed to travel at a maximum speed of 25 km/h and have to maintain a distance of 500 metres between each other, Near said. On some “problem” lakes, where ice is not thick enough, the speed limit is reduced to 15 km/h.

“It’s the longest school zone in the world,” Near joked.

Listening to the ice cracking

The ice road has none of the drama portrayed in the popular History channel reality show “Ice Road Truckers,” which put the territory on the map for many people around the world, Near said.

The ice road has none of the drama portrayed in the popular History channel reality show “Ice Road Truckers,” which put the territory on the map for many people around the world, Near said.

Dave Cook, a driver from Nova Scotia who’s been driving on the ice road for six years said the show sensationalized a lot of the aspects of life on the road.

“They show you what could happen if you do things you’re not supposed to do, which is possible but 90 per cent of the guys all behave themselves,” Cook said. “They’re telling you guys are awake for 36 hours, and are running up and down the roads. They don’t do that.”

Cook said it takes about 15 hours to get to the Ekati Mine, about 310 kilometres northeast of Yellowknife. Drivers stop midway at the Lockhart Camp, get their required sleep and then continue to Ekati the next day, he said.

“It’s something different, it’s unique, not everybody can do it,” Cook said about his reasons for coming back to the ice road year after year. “You see caribou out here and moose, and wolves, and wolverines.”

And Cook said he’ll never forget the first time he drove his truck on the ice.

“The first thing I did when I got on the ice, I opened my door and I listened to the ice crack, that’s all you hear,” Cook said, “and as long as you hear that, you’re good because the ice is adjusting.”

A few good men

Richard Bulley, assistant supervisor at the dispatch centre that manages the traffic on the ice road, said he too was attracted by the promise of a unique experience.

Richard Bulley, assistant supervisor at the dispatch centre that manages the traffic on the ice road, said he too was attracted by the promise of a unique experience.

“It’s a unique job, a unique location and a really good people to work with,” said Bulley, a retired Ontario Provincial Police hostage negotiator. “When I retired, I didn’t want to do a regular security work or these Mickey Mouse jobs. I was looking for something unique to do.”

Then a meeting with David Madder, another retired police officer, changed Bulley’s retirement plans.

Madder was the dispatch supervisor for the winter road and was looking for a few good men to help him run the operation.

“I gave up two weeks vacation in Florida and a golf trip to Santee, South Carolina, came to Yellowknife,” Bulley said chuckling, “go figure!”

And he’s been doing it for five years now.

“After 30 years of dealing with all the idiots on earth, we come up here and deal with some really good people, and it’s a lot of fun,” Bulley said. “And it’s only two months a year, so it doesn’t interfere with my golf course or the cottage life in back in Ontario.”

Bulley said most of all he gets to enjoy the feeling of camaraderie the ice road creates among the people who work there.

“It’s not like the open highway,” Bulley said, “there are no stoplights, there are no barriers out there, no guidelines other than rules and regulations. These guys really learn to work with each other and take care of each other.”

Quick Facts:

First year constructed – 1982

First year constructed – 1982

Original purpose – supply the Lupin Gold Mine at Contwoyto Lake, Nunavut Territory

Length – 600 kilometres (360 miles) to Lupin with route being 87% over lake ice

Width – 50 metres (160 feet) on lakes, narrower on portages (12-15 metres) 25-45 feet

Ice thickness – Engineer proven to support light vehicle loads at 70 cms (27-28 inches) increasing to full highway truck loads as the ice thickens, often exceeding 107 cms (42 inches)

Speed limits on ice: Loaded trucks – 25 km/hr (15 mph) with some areas 10 km/hr; empty trucks – 60 – 70 km/hr (35 mph) on “Express Lanes” – which are return (southbound lanes) built on larger lakes

Speed limits on land (portages): – Mandatory portage speed is 30 km/hr, with trucks having to slow to 10 km/hr on and off portage

Number of Portages – 64 portages are located along the route

Maintenance Camps – Three camps that can accommodate 49 personnel in each are located at Dome Lake, Lockhart Lake and Lac de Gras

Manager – Joint Venture Management Committee (JVMC) comprised of BHP Billiton Diamonds Inc., Diavik Diamond Mines Inc. and DeBeers Canada Inc.

Road Constructor – Nuna Logistics Ltd (main route), RTL Robinson Enterprises Ltd. (secondary route) are contracted by the JVMC

Engineering – EBA Engineering Consultants Ltd.

Security – Deton Cho /Scarlet Security Services, historically SECURECheck (2000 – 2009)

Historical Winter Road Statistics (2000-2011)

|

Year |

Operating Period |

Total Tonnes Hauled (northbound) |

Number of Truckloads (northbound) |

Days Open |

|

2001 |

Feb 5 – Apr 15 |

245,586 |

7981 |

70 |

|

2002 |

Jan 26 – Apr 16 |

256,915 |

7735 |

81 |

|

2003 |

Feb 1 – Apr 2 |

198,818 |

5243 |

61 |

|

2004 |

Jan 28 – Mar 31 |

179,144 |

5091 |

64 |

|

2005 |

Jan 26 – Apr 5 |

252,533 |

7607 |

70 |

|

2006 |

Feb 5 – Mar 27 |

177,674 |

6841 |

50* |

|

2007 |

Jan 28 – Apr 9 |

330,002 |

10,922 |

63 |

|

2008 |

Jan 28 – Mar 31 |

245,585 |

7484 |

55 |

|

2009 |

Feb 1 – Mar 22 |

173,195 |

4847 |

42 |

|

2010 |

Feb 4 – March 21 |

120,020 |

3508 |

36** |

|

2011 |

Jan 28 – March 31 |

239,000 |

6832 |

55.5 |

* Road shut down early due to thin ice conditions – approx 1200 loads had to be flown into the mines in the summer/fall of 2006

** Due to warmer temperatures, the joint venture was forced to adopt night time only hauling from March 3 to 16