U.S. to lease land in Alaska for oil and gas development

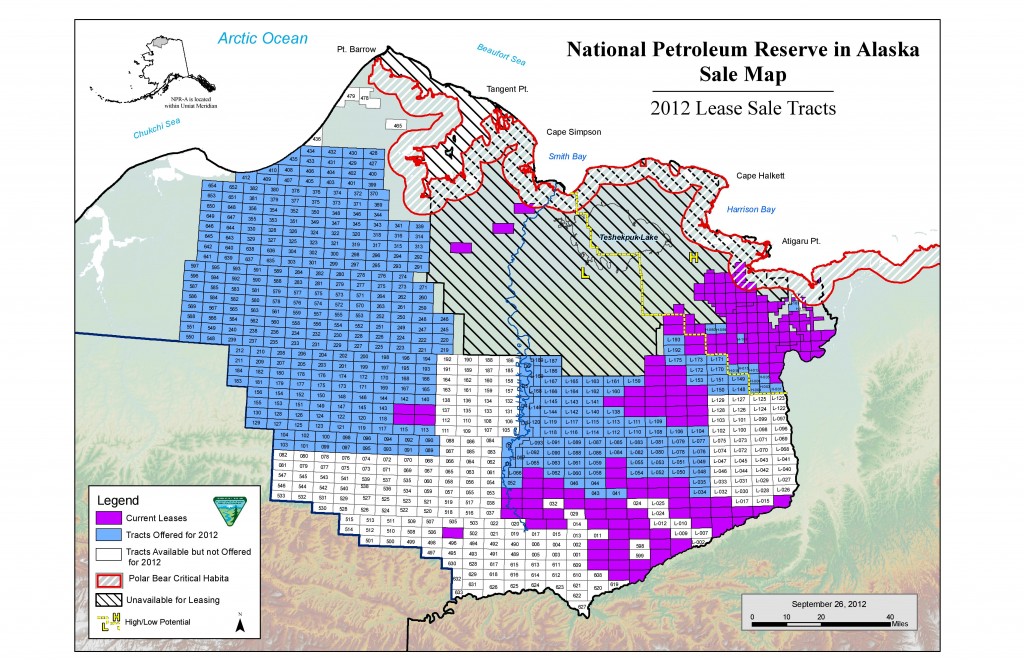

The U.S. Department of the Interior recently announced that the Bureau of Land Management will issue leases for 4.5 million acres of land in the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska for oil and gas development.

The November 7 lease sale will add to the 3 million acres offered up in the same area last December. Of that amount, 120,000 acres were leased through 17 bids. The main lease purchasers were ConocoPhillips and a company called 70 & 148 LLC, named after the latitude and longitude of Prudhoe Bay.

70 & 148 is an affiliate of Armstrong Oil and Gas, a little-known company in the world of giant multinationals like Shell, BP, and Exxon Mobil.

The website for Armstrong leaves much to be desired, and I could not even find a website for 70 & 148, which happened to be behind 11 of the 17 bids. It will be interesting to see if small companies dominate the upcoming lease sale or if the larger companies are more involved. In any case, the December 2011 lease sale reminds us that it is not always just Big Oil that is involved in the extraction of Arctic hydrocarbons. There are a litany of small players as well whose activities are not always as transparent.

In a press release, Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar stated, “The November sale is in line with the President’s direction to continue to expand domestic energy production, safely and responsibly. Since the President took office, domestic oil and gas production has increased each year with oil production higher than any time in eight years, and production of domestic natural gas at an all-time high.”

Much of the increased oil production is from the Bakken Formation in North Dakota, which is now the country’s second-biggest oil producing state after Texas. Oil production hit 700,000 barrels a day for the first time in August. There is a lot more oil in the Bakken Formation stretching through North Dakota and Montana than Alaska: estimates for the Bakken vary widely, but the USGS estimated in 2008 that it held 3 to 4.3 billion barrels. By contrast, the NPR-A is estimated to contain 896 million barrels (USGS). The North Slope as a whole, however, could hold a much larger amount of oil.

Land development

The oil and gas development in the NPR-A would occur on land, so it is not as prone to controversy as the recent offshore oil exploration undertaken by Shell in the Beaufort Sea. In fact, many in Alaska champion development of the new resources not just for the sake of having more production and more jobs, but also to keep the entire industry afloat. This is because the amount of oil flowing through the TransAlaska Pipeline System (TAPS) has decreased steadily since 1988, and the pipeline could face problems such as freezing if the volume drops below 550,000 barrels a day. The U.S. Energy Information Administration published an overview of the potential problems TAPS faces.

Underscoring the crucial nature of getting more oil to the pipeline, Senator Mark Begich (D-Alaska) stated in a September press release, “I made it clear today Alaskans see NPR-A as a critical bridge between offshore development and filling the pipeline…As Secretary Salazar said yesterday, our country needs NPR-A to fuel our future. Over the next three months, I will be working double-time to find the right balance in the NPR-A for Alaskans where we’re able to deliver on- and off-shore resources to the Trans-Alaska Pipeline – along with jobs and revenue for Alaskans and for state.” I would be curious to know if rising temperatures in the Arctic are making it less urgent to get more oil flowing through the pipeline, though. Additionally, it is interesting to contrast the problems Alaska is facing – essentially a crunch to get more oil to the pipeline – with those of Alberta and its oil sands, where they soon will not have enough pipelines to get all of the hydrocarbons they want to market.

New leases

As new leases are put up for auction, Shell is negotiating with the Department of the Interior to extend its leases in the Barents and Chukchi Seas, as they are set to expire in 2015. The 2012 drilling season is already over, and Shell has barely made a dent in its plans (though it has made a major dent in its wallet, to the tune of $4.5 billion). Legal cases, regulations, technical difficulties, and weather have all held up Shell’s progress. Other companies are surely waiting in the wings to see how the negotiations proceed with the DOI. If Shell were not to receive an extension, this would be disappointing to many other hydrocarbon companies. Carrying out any activity in the Arctic always takes much longer than planned, and companies have to factor this into their plans and their budgets when drilling for oil.

Finally, on the other side of the Arctic, Rosneft is gearing up to become one of the world’s largest oil companies. It is in talks with BP to purchase its stake in TNK-BP, the joint venture that is developing Russian Arctic offshore oil resources in places like the Kara Sea. If the deal goes through, the New York Times reports that Rosneft would become “the world’s largest publicly traded oil company in terms of crude oil production.”

In 2011, PetroChina was in first place, Rosneft in second, and Exxon Mobil in third. A bigger Rosneft would produce at least 4.5 million barrels a day and control 45% of Russian oil production. The Russian oil industry would then have a much different makeup than that of the United States. Putin is attempting to create “national champions” in strategic industries like oil and gas in order to advance Russian interests.

An oil monopoly would be able to keep prices fairly low at home, which could augment Putin’s power, much of which is based on satisfying the public through low energy prices. Ostensibly, higher prices abroad could subsidize low prices within Russia. However, this is easier said than done, for oil is a globally traded commodity. Unlike natural gas, whose price varies a lot from country to country because the commodity is not very easily transported, oil is fluid and put on tankers to be traded around the world.

It’s not so simple for a country or company to set the price of oil as Gazprom can do with gas. If the price of a barrel of oil in Moscow or Vladivostok eventually has to rise, this could spell trouble for the Kremlin. Thus, Putin should be wary on placing too much faith in the hands of one operator. Contrariwise, the U.S. should keep close tabs on all of the companies at work in its Alaskan backyard.

News Links

“BP Board weighs up Rosneft offer,” Financial Times