Blog: The long road from Yakutsk

Worries about this summer’s upcoming cruise through the Northwest Passage by the 1,000-passenger, 600-crew Crystal Serenity have dominated Arctic headlines this week. The cruise ship plans to sail from Anchorage, Alaska to New York via Canada’s Arctic sea route over the course of 32 days.

It will stop in several destinations in Greenland on the way, too, as the ship exits the Northwest Passage via the Davis Strait. (Alert for those keeping a watch on Maine, which I once wrote has the potential to become the “next near-Arctic state“: Crystal Serenity will dock in the Pine Tree State’s coastal town of Bar Harbor.) The luxury ship’s “cruise-only fares,” which don’t include add-on tours by helicopter, zodiac, kayak, or speed boat, start at the eye-watering price of $21,855.

Crystal Serenity ‘s full itinerary, which is likely keeping the coast guards of the U.S., Canada, and Greenland up at night, is available here. Canada-based CBC News quotes Michael Byers, a professor at the University of British Columbia, as saying, “If the ship sinks, then that would actually break the Canadian search-and-rescue system.” With extremely limited medical facilities in the Canadian Arctic, poor communication systems, and vast distances, search-and-rescue teams would face enormous challenges in responding to a disaster involving a ship of Crystal Serenity’s size.

The Guardian referred to the ship’s journey as a potential “new Titanic.” A more apt comparison might be the sinking of the Estonia ferry in a heavy storm in September 1994. Despite sailing from Tallinn to Stockholm in the Baltic Sea, one of the world’s most heavily trafficked maritime areas, 852 of the 938 people onboard died – largely due to drowning and hypothermia compounded by a poorly coordinated rescue effort. The water temperature in the Baltic was around 50–52 °F. The Northwest Passage is much colder than that.

1,000 if by sea, a few if by land

While the media fixates on the vulnerability of the lives of the 1,000 affluent tourists who will cruise the Northwest Passage this summer, hazardous journeys take place in the Arctic every day. They just usually involve fewer wealthy people, with passengers tending to pay a fraction of the cost of an Arctic cruise to move from point A to point B. Importantly, people living in (rather than visiting) the Arctic and sub-Arctic often have the capability for self-rescue, while a hulking cruise ship might not.

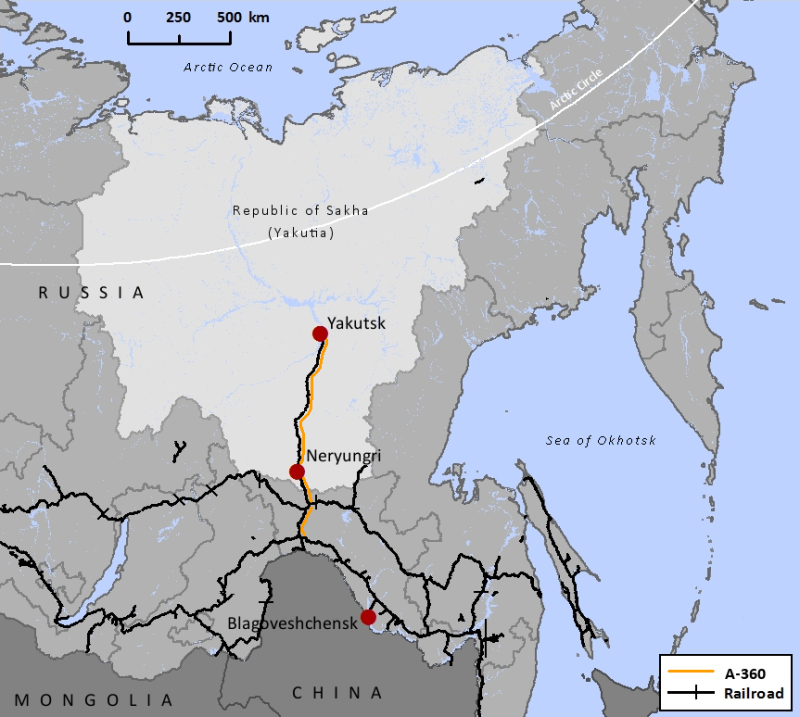

In early March 2016, for 3500 rubles (about $50), I took part in one of these nail-biting but quotidian journeys in order to travel from Yakutsk, one of the world’s most remote cities, to Neryungri, a coal-mining town built during Soviet times. “The road is terrible and long,” people in Yakutsk warned me. “It’s dangerous out there,” others alerted. And it would be impossible to count the number of people who asked me incredulously, “Why don’t you just fly?”

My ultimate destination was Blagoveshchensk, on the Amur River border with China, and there are direct flights between Yakutsk and the Russian border city that take about two hours. Why would any sane person want to travel in a cramped van with 11 other passengers in a journey that some people cautioned could take 16 hours, sleep overnight in a coal-mining town, and then take a 22-hour train the next day to the city of Belogorsk – which still was two hours by taxi from Blagoveshchensk?

First, I knew aviation in the Russian Far East was risky as well. Second, while the hours seemed long – two hours by air versus 40 hours by ground – the protracted nature of travel in the North, a world without interstates and high-speed rail, is part of its appeal. To understand Siberia and the Russian Far East requires experiencing its unrelenting and unforgiving vastness on the cold hard ground.

Third, a few people gave me hope that I would not, in fact, be swallowed up by the taiga. One woman I met informed me, “The road is better in winter than in summer.” This made me think that I might as well give the journey a shot now, for when else would I be in Yakutia in the dead of winter? She added, “The mountains, the sky – it’s beautiful.” She had taken the road once with her family in a car to go visit relatives in a village “not far from Yakutsk,” which she later clarified was about six hours away by car. Russians’ gauge for small distances is perhaps even more warped than Americans’.

Lastly, when a mammoth scientist working at a museum in Yakutsk, once informed of my plans, told me that the most important thing to remember was that I “bring a lot of buterbrod (sandwiches),” I knew things would be just fine. I decided to go by ground.

Driving in circles

“Text me the day before with what time you want to leave, and we’ll find a taxi for you.”

So instructed a contact I’d been given by a colleague in order to arrange transportation to Neryungri. The day before my trip, I texted the appropriate number, requested the front seat, and waited for a response. “Your taxi will come between 8am and 10am,” I learned.

The next morning, I packed my bag, loaded up on sandwiches, and began waiting for the taxi. Would it be a van? A car? A jeep? I had no idea. I just knew the license plate to look for – this is how the marshrutka, or shared van, system works in many Russian cities.

Around 9:15 am, a black van emblazoned with two roaring tiger heads rolled up to my hotel. I hurried downstairs in all my winter gear. My bag was thrown in the back of the monster van, which looked about ready to conquer whatever nature threw at it. I took the front seat and stared down at all the cars in front of me as we pulled out of the parking lot. Many vehicles in Yakutia are raised up high on their tires because of the snow and the poor conditions of the roads. Three Orthodox icons, a dangling U.S. dollar sign, and the flags of Yakutia decorated the dashboard.

For the next three hours, we drove in seemingly endless circles around Yakutsk picking up passengers. Most were ethnic Russian men traveling alone. Neryungri, unlike Yakutsk, is mostly ethnic Russian. A few women got in, and one Yakut man.

Finally as the clock approached 12:30 pm, the driver repacked all of the bags on top of the van. He collected our fares in cash and informed us of the journey ahead. “We will stop for lunch, dinner, and smoke breaks,” he announced. “And buckle your seatbelts.” The passengers groaned. Wearing seatbelts is not the norm in Russia.

My fellow passengers sat nonchalantly in their parkas while I was sweating in my thermal wear. Prior to coming to Siberia, everybody had warned me about the cold I’d encounter, but no one had told me how hot it would be indoors everywhere. Whether in a hotel, a restaurant, or a car, dry heat at a temperature that feels like 80°F is constantly pumped out. What’s worse, it’s impossible to crack the windows because the temperature outdoors is -30°F. Instead, I just sweltered. One researcher from Finland who had rode in a van from Yakutsk to Neryungri a few years prior had mentioned, “The worst thing about the journey is that it’s so hot. You’ll be wearing a parka while wishing you were in a swimsuit!”

That much was true.

Embarking on the journey

Speeding out of Yakutsk, the driver put the pedal to the metal. Five minutes later, a policeman ordered him off the road. He hastily pulled his vehicle registration papers out, went outside for 10 minutes while the other passengers excitedly took advantage of this unplanned smoke break, and then returned. “Shrtaff” (“fine”), he grumbled, as the other passengers chuckled. We hit the road again. The buildings of Yakutsk receded in the mirror, replaced by a blanket of trees and snow. I asked the driver how long it would take to get to Neryungri, and he replied that he normally makes the drive in 10-12 hours. That was better than I expected.

We stopped in one small village and picked up an additional passenger. Then the journey really began. The clear blue skies and strong sun were making me drowsy, so I fell asleep for about 30 minutes. I woke up when our vehicle began to slow and descend down a bumpy road. I looked out the window to my right and noticed a flat plane of white snow. Shaken out of my stupor, I realized it was the frozen Lena River – and we were about to drive across it from the little village of Bestyakh.

Frozen rivers are another reason why journeys are faster in Yakutia in winter. Unlike in summer, vehicles don’t need to wait for ferries to take them across – they can just drive whenever on rock-hard ice roads. Some of the roads, like the one we crossed, are trafficked enough that the government paves and grits the ice and erects road signs.

Winter roads, however, are in danger due to climate change. As warming temperatures open up the waters of the Northwest Passage, it thaws the ice and permafrost on land, as my former colleague Scott Stephenson, a professor at the University of Connecticut, has shown. A taxi driver in Yakutsk had told me a few days before, “By September 1, it used to be cold. Now it’s not cold until October. And it’s warm in February already – you see now, it’s already -25°C. (Yakutians also have a warped sense of cold temperatures.) It used to be -40°, -50° often. Now, that happens only three to four days a year.”

A silver mirage

Safely across the Lena, we ascended back up the other side of the river, passing river boats that would be frozen in place for another few months. This was a bizarre sight for me. The driver cracked his window to have another smoke. Georgian chanting laid over techno beats blared through the speakers, the song being one of over 500 MP3 files lined up for the journey. Drivers make sure to stock up on music because there sure as hell isn’t radio in the middle of Yakutia.

After speeding through the sleepy village of Kachitkattsy, we turned south onto the two-lane A-360 highway that connects Yakutsk (or at least the riverbank across from it, as there is no bridge that would serve as the final link to permanently connect the capital to the Russian highway network) to the outside world. There were not many vehicles on the road, which was also in better condition than I had envisioned. Whereas Americans have a tendency to exaggerate the positives, maybe Russians tend to exaggerate the negatives. Yet there were a ton of trucks on the road going to and from Yakutsk. We’d pass by trucks carrying cargo containers or enormous cylinders of gas every so often, some of them with big Chinese characters on the front betraying their country of manufacture.

At some times, the road cut impossibly long straight lines through the forest. At other times, it curved gently around rolling, tree-covered hills. Occasionally on the right side, it was possible to catch an enticing flash of silver as the railroad tracks of the newly built Amur-Yakutsk Mainline came into view. But the smooth speed promised by its shining rails is a mirage to individuals traveling on the bumpy highway, for north of Tommot (400 kilometers to the south of Yakutsk), the line is only open to cargo trains. Most people embark or disembark from the train at Neryungri, as it is faster to continue to or from Yakutsk by car, like I was doing. Construction on the Amur-Yakutsk Mainline, which connects to the Trans-Siberian Railway, was completed about two years ago. Unlike its name, however, the railroad does not terminate in Yakutsk. Instead, like the A-360 highway, it terminates on the western bank of the Lena River in the town of Nizhny Bestyakh.

Lunch and talk of the future

After a couple of hours of driving, we stopped for 30 minutes at a roadside cafe called “Cafe Legion” for lunch. The van pulled into the parking lot, where there was also a hotel, car repair shop, and bathhouse (banya), and was left to idle in position. Cars are rarely turned off if the stop is less than an hour because of the risk of a frozen engine. I briefly visited the outhouse (a frozen, but fortunately odorless, house of horrors) and then walked towards the cafe. A fellow female passenger chastised me for not wearing my hat. I needed to cool down, though, after enduring the searing temperatures inside the van.

Inside the restaurant, borscht, meat cutlet, pickled salads, and big steaming mugs of tea were all on offer for no more than a dollar or two. Journalist Matt Taibbi once quipped that Russia is a country of “eleven time zones of bad food.” What’s most remarkable to me though is not the uniform mediocrity of the cuisine, but rather that Russian cuisine has penetrated even into the deepest reaches of Siberia. I ordered a cup of tea, handed over some coins, and the cashier barked into the kitchen, “Black tea!”

Sitting with the driver at his table, I drank my tea and ate my packed sandwiches. He worried that I wasn’t getting enough to eat, but I reassured him that I’d eat properly at dinner. We talked about his life, which was a typically cosmopolitan one within the Soviet orbit. Born in Kazakhstan and raised in Ukraine, he now lives in Neryungri. Our conversation moved on to traveling – he’d been to to Thailand and Egypt on vacation, and his mother went on holiday to Kamchatka. This wild land of volcanoes that spits out into the Pacific on Russia’s easternmost edge appears to have captured the imagination of many Yakutians much the way many Americans think of Alaska. I asked more about his family, and he proudly described how his daughter was studying chemistry in Novosibirsk, Russia’s third largest city. I later inferred that her studies were probably related to the oil industry after the driver observed, “You know, the future is oil and gas. For all of Russia.”

An accident

Hours more passed by on the taiga. The driver aggressively passed legions of trucks, coming close up on their rear bumper before swerving around them in the opposite lane. The light slowly softened over the snow. Sting’s “Desert Rose” blasted over the stereo. As we came over a large hill, a big-rig sprawled across the highway came into view. It was still right-side up, but had somehow lost its grip on the road as it was ascending and had come to rest across both lanes, blocking traffic in both direction. The mishap must have happened just a few minutes before we arrived since cars and trucks were only just starting to pile up on each side.

The driver brought our van to a halt and jumped out to investigate. A few minutes later, he came back, called on all the men to help him, and borrowed shovels from the other trucks that were idling. With their shovels, the men tried to widen the highway by shovelling away the snow from the shoulder. Ten minutes later, the first car tried to go around the truck, but the passage was still slightly too narrow and the “road” underneath it too soft. The men decided they would instead push the cars through. About ten of them pushed one car after another, and then it was our van’s turn. The driver excitedly told all the women to get inside, but nobody wanted to. “I’m afraid!” one Russian woman proclaimed, her blue eyes wide open. We decided to stand outside and watch as the men pushed our wobbling, top-heavy van precariously around the stuck truck. Twenty seconds later, the van was back on tarmac. We cheered and ran around the truck and piled in again for the second half of the journey.

Nearly there, by Siberian standards

Once we made it around the marooned big rig, it began to feel like we had almost reached our destination even though it was still about six hours away. The light was fast dimming. We sped by road workers on the side of the highway warming their hands over big piles of blazing sticks and branches that they had lit on fire in an elemental contrast of fire and snow. I began to doze as Ace of Base came on the stereo. Stars crept out of the indigo sky one by one, eventually numbering what appeared to be a billion in a place without light pollution (even though surprisingly, only 4,548 stars on average are visible from one hemisphere at any time).

I woke up from a nap in Tommot, where we ate dinner in another roadside cafe. Outside sat half a dozen trucks, many carrying weighty loads of lumber. Before eating, a passenger from Aldan and I went to look for the facilities. We were directed next door to a small building. Inside, the attendant informed us that it would cost 30 rubles to use the toilet. This is a fair amount of money in a place where a cup of tea or instant coffee costs less than that. The lady from Aldan exclaimed exasperatedly, “Who pays 30 rubles for a toilet? Rich people?”

We used the bathroom and washed our hands in the immaculately clean sinks. A black cat sat on top of a washing machine that was in use. Here at this fancy rest stop, one could shower, wash your hands in a sink with foam soap, do laundry, and, most luxuriously of all, use a flush toilet with toilet paper included – a rare sight in Russia. Much the way some people might take extra ketchup packets in America, after a few weeks in Russia, the sight of a plush toilet paper roll makes you want to tear off a few dozen squares and stuff them in your pocket.

Back in the cafe next door, for just a few rubles more than entrance to the bathroom, I ordered some cottage cheese pancakes drizzled in condensed milk and potatoes broiled in butter. Grown in Siberian soil, the tubers were incredible. Never underestimate the power of the humble potato in Russian cuisine.

After people had gulped down their last noodles and sips of tea, we resumed our journey. The next stop was Aldan, a gold-mining town where about half of the passengers got out. It felt like re-entering civilization, almost. Across a distance of 600 kilometers, we had passed no more than a handful of villages. In contrast, Aldan boasted a couple hotels, some neon lights to electrify the dark winter night, several mini-markets, and the Russian North’s ubiquitous heating pipes that are built overground instead of underground to avoid building in permafrost.

The van’s digital clock beeped that it was 9pm. I closed my eyes again. I opened them once only to find our van in a cloud of swirling snow and dust about a meter behind a huge truck as the driver prepared to pass in the oncoming lane. It would be better for my blood pressure, I thought, if I continued to keep my eyes closed.

“Are you hungry?” the driver asked me a couple of hours later as we neared Neryungri. “Come over to my apartment – my wife is already preparing borscht.” I laughed and politely declined his offer. All I wanted was a bed on steady ground. Food could come second – and besides, the pancakes and potatoes were still tiding me over.

Around 12:00 am, we rolled into Neryungri, a town of about 62,000 people built on a series of hills. We dropped a few passengers off at the train station. They planned to sleep there until the morning train towards Moscow, 5000 kilometers away. I ran in and with the assistance of another passenger, bought my ticket for the next day’s evening train towards Khabarovsk, the biggest city in the Russian Far East.

Once we crossed into town, the familiar nine-story apartment buildings built under Brezhnev peppered the landscape under the dark of night. One could extend Matt Taibi’s observation to say that Russia is a country of “eleven time zones of bad food and nine-story apartment blocks.” The driver began weaving in and out of the labyrinth of apartment buildings as he dropped passengers off. At one intersection, we waited for the light as a group of carousing teenagers crossed in front of us without a seeming care in the world. “This town can’t be so bad,” I thought to myself.

Finally, with only a few people left in the van, we rocketed up the unnecessarily wide main drag, named after Lenin (like so many main streets in Russia). The driver hopped out and made sure that I had no problems checking into the hotel, which had an incongruously neo-tropical-kitsch vibe to it. The only problem I had was that my thermos had appeared to have fallen out of the side of my backpack somewhere between Yakutsk and Neryungri while stored on top of the van. The driver apologized profusely and said there was a chance the thermos might be in the back of the van, where my backpack had initially been placed. I thanked him, went into my room, and unpacked a few clothes, frozen stiff from being exposed to sub-zero temperatures for 12 hours.

The next day, the driver miraculously found my thermos in the back and dropped it off at my hotel. As I was out at the time, he sent me a perfunctory text message in Russian: “Bottle returned.” Russians underestimate the quality of their own roads, while foreigners underestimate the kindness of strangers in this forbidding land. One Yakutian woman told me, “We always help each other and look out for each other. It’s a matter of survival because if you don’t, in this cold, you could die.”

This post first appeared on Cryopolitics, an Arctic News and Analysis blog.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Canadian province of Quebec announces plan for northern development, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Helsinki Airport “best in northern Europe”, Yle News

Norway: Production uncertain beyond Q2 at iron-ore mine in Arctic Norway, Barents Observer

Russia: Mining accident death toll rises to 36, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Relocation of Arctic town underway in Sweden, Radio Sweden

United States: 1,000 experts converge in Alaska for Arctic events, Alaska Dispatch News

Good to see that nobody got hurt from the truck accident. Seems like you had a good trip. I liked the laundry stop the most. It looks so nice and clean – I’m pretty sure I would like to try that too.