Blog: Poirier’s Revenge – The map of Canada has the wrong Arctic boundaries. No, really.

When Polar Knowledge Canada was created out of the ashes of the Canadian Polar Commission in 2015, it published a fancy new version of the North Circumpolar Map, with its name emblazoned around the edges, to help with its rebranding.

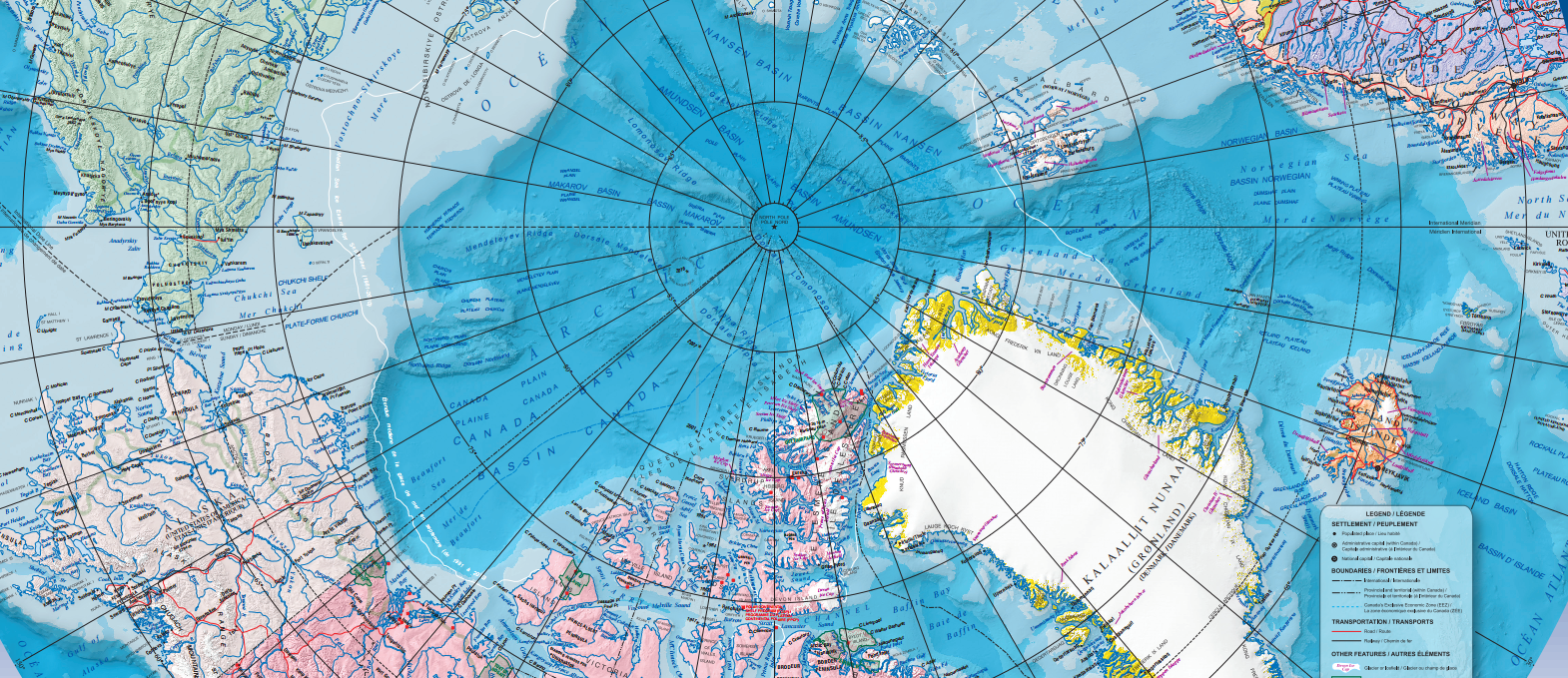

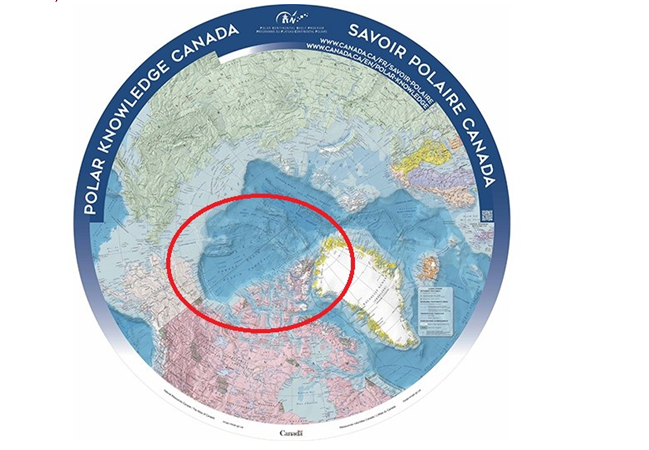

These have been shared freely at many Arctic and polar conferences and events since, and I’ve picked up a handful of the maps on four separate occasions, handing them out to colleagues who appreciate the unique polar projection. I also hung one on my office wall, and probably walked by it hundreds of times until one day this Summer when I looked, really looked, at the map and noticed a big black international boundary line creating a pie slice like shape from the Yukon-Alaska boundary all the way up to the North Pole.

The official Canadian map of the Arctic region is using what’s known as the sector theory to delineate its Arctic maritime boundaries. Which is perplexing since our official legal position does not, and never has.

Pie chart

Canada’s claim to its northern territory extends from the transfer by Great Britain to Canada in 1870 of “all lands and Territories within Rupert’s land” and a further transfer in 1880 of “all British Territories and Possessions in North America, not already included in the Dominion of Canada, and all islands adjacent to any such Territories or Possessions.” This declaration being fairly vague with regards to Canada’s extent in the Arctic Archipelago, Senator Pascal Poirier proposed on February 20, 1907 that Canada make a formal declaration of possession of the lands and islands extending to the North Pole, based on the principles of the sector theory, stating that:

Having no legal basis or practical advantage, no one seconded his motion. It was not voted on in the Senate, did not reach the floor of the House of Commons, and it never became official government policy, although it was revived in discussions about Canada’s Arctic sovereignty on several occasions.

Canada’s legal position on the extent of its claim over Arctic waters remained vague until 1970, when Pierre Trudeau introduced the Arctic Waters Pollution Prevention Act in response to the controversial voyage through the Northwest Passage of the Manhattan. It extended Canadian jurisdiction in Arctic waters to 100 nautical miles in order to enforce certain pollution standards on Vessels, and extended its territorial sea from 3 to 12 nautical miles. These later became enshrined as international law with the passing of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Canada’s Arctic claim was further and definitively outlined in a speech by then External Affairs Minister Joe Clark in 1985. He called Canada’s sovereignty over its Arctic “indivisible” and encompassing “land, sea and ice”, and announced the establishment of straight baselines around the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, effective January 1, 1986. This essentially identifies all of the waters within and between the islands of the Arctic Archipelago as internal Canadian waters. (There is some dispute whether the Northwest Passage constitutes an international strait or internal waters, and I can’t bring myself to get into that debate again.)

You can see the Canadian Hydrographic Service’s Canadian Arctic Islands and Mainland Baselines map here.

Legal scholar Donat Pharand outlined all this in his seminal 1988 book on the subject, Canada’s Arctic Waters in International Law, and the account can be found on several Government of Canada websites, for example at the Ministry of Defense and in an internal research paper prepared in 2008 for the Parliament of Canada. Quoting the Ministry of Defense:

A piece of the puzzle

So why in the world is Polar Knowledge Canada publishing boundaries that are not officially claimed by Canada?

To be fair, Polar Knowledge does not delineate Canadian international boundaries. It got its map from Natural Resource Canada’s (NRC) Atlas of Canada. Indeed, Canada is claiming erroneous boundaries not just on its Polar Knowledge Canada map, but on all of them. As best I can tell, from a quick look at NRC’s online selection of historical maps, the sector delineation to the North Pole was drawn in to our official maps sometime between 1905, when the line does not appear, and 1949, when it does. I imagine it is difficult and time consuming to change Canada’s boundaries on its official maps. But why it wasn’t done so in 1986, after Cabinet had adopted an order in council to draw straight baselines around the Arctic Archipelago, or at any time since, is a puzzle. If I were to speculate, I might suggest it has something to do with this country’s unhealthy obsession with Arctic sovereignty and an unwillingness on someone’s part to reduce, even symbolically, the amount of northern territory we claim to be ours.

À la mode

We continue to use the principles of the sector theory in the Arctic in other ways, for example to delineate the Search and Rescue areas of responsibility of Canada, the United States, Denmark, Russia and Norway. And Russia’s UNCLOS extended continental shelf submission defers to the principle, stopping abruptly at the North Pole despite its having no geological significance (Denmark was more blasé, claiming a big chunk of continental shelf on the Eastern side of the hemisphere; Canada has not yet submitted its claim.)

But it has no rightful place in either Canadian or international law as a determinant of international boundaries. The drawn lines on a map should reflect, not determine, Canadian policy. We are well overdue to correct this.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Mapping the Arctic’s future while erasing its past, Blog by Mia Bennett

Denmark: Denmark claims North Pole, Barents Observer

Iceland: Revisualizing the Cryosphere, Blog by Mia Bennett

Norway: Norway and Russia adjusting border line, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Swedish ships mapped at bottom of sea, Radio Sweden

Russia: Rosneft prepares seismic mapping of east Arctic waters, The Independent Barents Observer

United States: Mapping and distorting the Arctic, Blog by Mia Bennett