Interview – Hair samples from Franklin expedition member show high lead levels

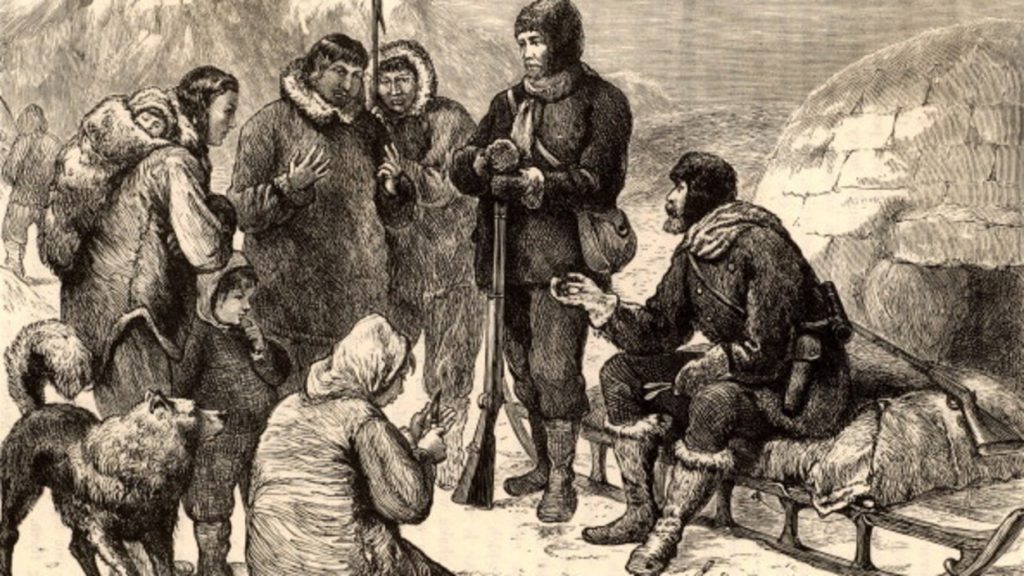

When Sir John Franklin left Britain with two ships and 129 sailors in 1845, it was to be an epic adventure to discover the fabled Northwest Passage to the Orient. Possibly the most prepared exploration of the Canadian Arctic at the time, what it became was an enduring mystery of their fate.

Bits of information came out over subsequent decades of searching, including the only very recently discovery of their ships, which has only served to further heighten the mystery.

Since then science has discovered and proposed that high lead levels in their bodies likely either slowly poisoned them or seriously affected their thinking process – or both – leading to disastrous and ultimately fatal decisions by the crew.

Not the main cause of disaster

This newest study shows lead levels may have contributed to the tragedy, but were not the main cause of the disaster.

Lori D’Ortenzio (PhD) is a researcher in the Department of Anthropology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario where the study took place.

The findings of the McMaster researchers was recently published in the Journal of Archaeological Science Reports under the title, “The Franklin expedition: What sequential analysis of hair reveals about lead exposure prior to death” (abstract Here).

The research involved hair sample from a crew member, Henry Goodsir. whose body had been discovered in the Arctic in 1869. He died somewhere between 1846 and 1848. Brought back to England, the body was buried in a memorial to the lost expedition. Recent renovations in the area required the body to be moved which provided an opportunity to take hair samples for analysis.

What hair samples reveal

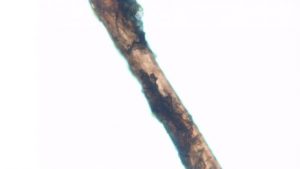

D’Ortenzio points out that earlier testing on crew members bodies involved tooth and bone samples which showed high lead levels. These however indicate only lead exposure over decades-long time periods. The advantage of hair samples she says, is that hair grows about 1-cm per month and can provide chemical analysis in the months before death or longer, depending on hair length.

Scientists have long speculated that the lead water pipes in the ships, lead content in medicines, and lead solder sealing tinned food resulted in high lead content being consumed by the crew.

If there was a sudden increase in lead exposure during the trip or in the months the ships were trapped in ice, this would have been evident in the new analysis.

The researchers had a 3-cm sample of hair thus the final 3 months of his life.

The lead content was similar to that of previous testing for lead contamination of other crew members bodies which provided information on long-term exposure. This test of hair however showed similar exposure levels, thereby showing no sudden or significant increase in lead consumption from life on the expedition, and so dispelling the theory that a sudden high lead contamination from water pipes and tinned food led to their deaths.

Thus the researchers conclude that while lead may have been a contributing factor in the bad decisions by the crew, it was not the main reason for the ultimate loss of all those on the expedition.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: ‘Amazing’ archeological find in northwest Canada’s melting ice patches: an intact atlatl dart, CBC News

Finland: Archaeological sites targeted in Finland, Yle News

Norway: Roald Amundsen’s Maud back home 100 years after setting sail from Norway, CBC News

Russia: First icebreaker to reach the North Pole ends her days in a scrapyard, The Independent Barents Observer

United States: Historic buildings crumbling in Anchorage, Alaska face an uncertain future, Alaska Public Media