Scientists surprised to discover meteor exploded over Bering Sea in December

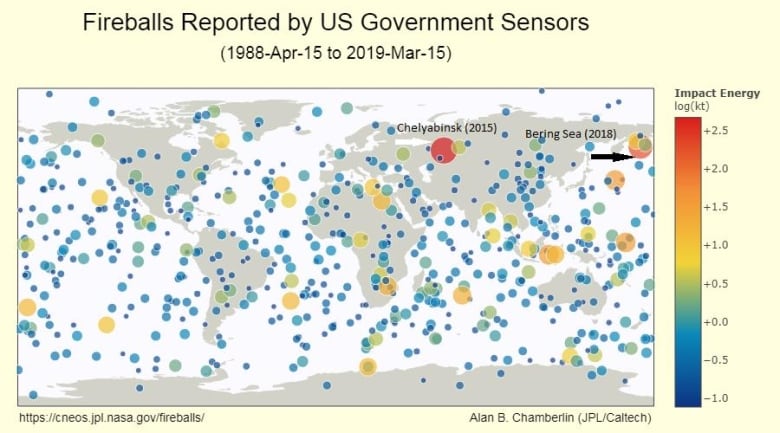

On Dec. 18, 2018, a large meteor streaked across the sky over the Bering Sea before exploding with 10 times the strength of the atom bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima in 1945.

Despite having an estimated diameter of 10 metres, the meteor entered our atmosphere unnoticed by astronomers at an estimated speed of 32 kilometres per second. It exploded with the energy of 173 kilotons of TNT, 300 kilometres off the coast of Kamchatka, Russia.

“It’s an unusual event,” said Peter Brown, a meteor expert and professor of physics and astronomy at Western University. “We don’t see things this big very often.”

The explosion was initially detected by the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO) shortly after it occurred. The organization looks for signs of potential nuclear missile activity. It does so with the help of monitoring stations around the world that measure infrasound, which is acoustic waves with low frequencies.

However, because it wasn’t a nuclear concern, the group simply catalogued it and moved on.

The blast went unnoticed by astronomers who track meteors. Almost three months later, Brown learned about the explosion while looking at CTBTO’s data. At the same time, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Cali., also added the Bering Sea explosion to its online fireball database. The blast received significantly more attention this past weekend at the Lunar and Planetary Space conference held just outside Houston.

Airburst over Bering Sea (58.6N, 174.2W) on Dec 18, 2018 @ 2350 UT detected by >16 infrasound stations worldwide. Based on periods in excess of 10 sec, minimum yield is tens of kT range – could be ~100 kT. Probably most energetic fireball since #chelyabinsk @WesternU

— Peter Brown (@pgbrown) March 8, 2019

Seen from space

Satellites confirmed the meteor’s path and explosion with images from space.

Watch as satellites captured the dust trail left after a large meteor broke up over the Bering Sea on December 18, 2018.

If there had been anyone in the vicinity of the meteor, they would have heard a massive explosion, similar to the meteor that exploded in the skies over Chelyabinsk on Feb. 15, 2013, Brown said. In that case, roughly two minutes after people witnessed the meteor, an airburst caused windows to explode, injuring 1,000 people.

The Chelyabinsk meteor entered at roughly 19 km/s, which Brown said is a little more typical for meteors of this size.

Brown has some reservations about JPL’s estimate that this latest meteor was travelling so much faster, at 32 km/s.

“My suspicion is that the velocity is too high,” he said. “But I have no data to support that.”

He points out that a recent study published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society compared velocities of meteors reported by JPL and ground-based observations. The paper found that the velocities reported by JPL have a large margin of error.

Cosmic shooting range

As Earth moves through space, it is constantly bombarded with rocky objects left over from the formation of our solar system. We see small grains of dust burn up in our atmosphere as meteors streak across the sky. But larger ones can enter the atmosphere without burning up completely, with pieces raining down on the ground (once they reach the ground, they are called meteorites). Large ones that are about 10 metres in diameter hit once every decade or so.

There are asteroids and comets that cross Earth’s orbit, referred to as potentially hazardous objects (PHAs), but astronomers around the world are keeping a close eye out for them.

“The public should not be concerned,” said Canadian Paul Chodas, manager of NASA’s Center for Near-Earth Object Studies at JPL. “Because these events are normal. Asteroids impact Earth all the time, though it’s usually much smaller than this size.”

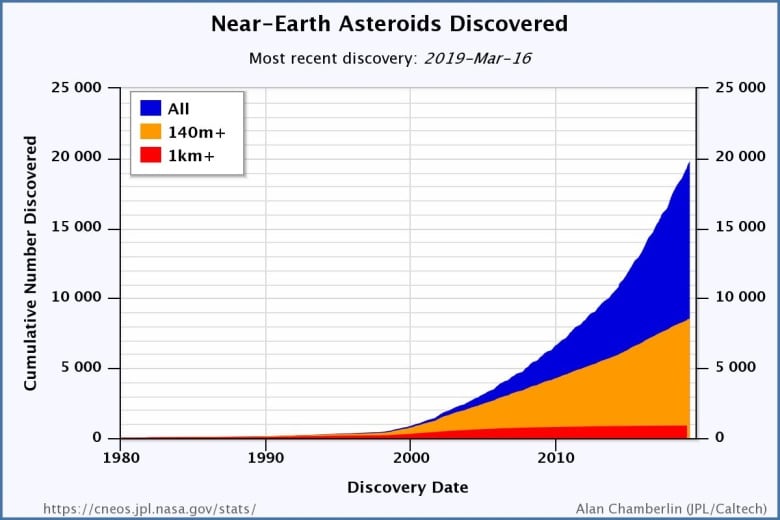

NASA is constantly monitoring the skies for these near-earth objects. Experts estimate roughly 90 per cent of objects in our solar system that are one-kilometre wide or larger have been found, and the U.S. Congress has set a goal of discovering 90 per cent of objects 140 metres in diameter or larger.

Approximately 2,000 near-Earth objects are discovered every year, Chodas said.

The only reason the one over the Bering Sea wasn’t detected is because it came from a northerly angle, where fewer telescopes are focused.

Once in a while you may hear or read about an asteroid passing “dangerously” close to Earth, such as asteroid 2019 EA2. This 24-metre-wide rock will pass within the moon’s orbit at 9:53 p.m. on March 21, but it will still be more than 300,000 kilometres from Earth.

If there is an asteroid that poses a danger to Earth, scientists would likely know about it far in advance.

For now, astronomers continue to scan the skies, with newer telescopes that will be able to see dimmer objects and farther out into space.

“In time, eventually they will all reveal themselves,” Chodas said of the near-Earth asteroids. “It’s just a matter of continuing to search for them.”

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: What ‘young’ Arctic rocks tell us about origins of the Earth and Moon, Radio Canada International

Sweden: Meteorite from Arctic Sweden fetches thousands at auction, Radio Sweden

United States: New map shows what Bering land bridge looked like 18,000 years ago, CBC News