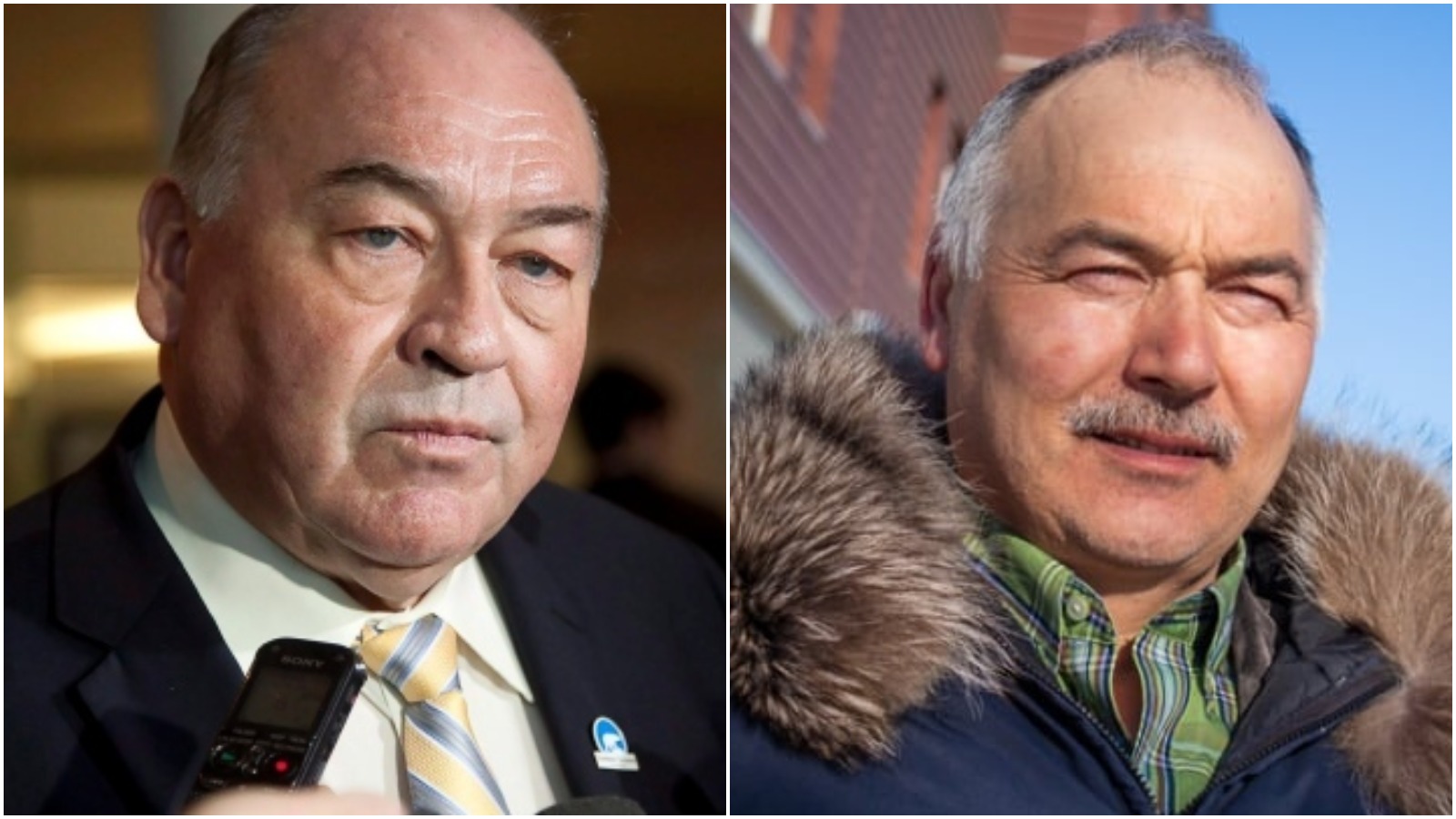

PMs from Canada’s central, eastern Arctic share conservative counterparts’ frustration with Ottawa

Two of Canada’s territorial premiers say they share the frustrations of the growing consensus of conservative premiers who oppose Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

While not counting themselves among the resistance — a term Maclean’s magazine coined in November to describe a coalition of conservative provincial premiers and the federal party’s leader Andrew Scheer who oppose Trudeau — the territorial leaders say they share their concerns about the carbon tax and Ottawa’s energy policy.

On the night Jason Kenney and the United Conservative Party swept to power, the incoming Alberta (Prairies) premier climbed out of his Tory-blue Dodge Ram pickup and greeted sign-waving supporters.

Kenney thanked premiers in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario and New Brunswick — all conservative-helmed provinces. But the premier-designate also singled out Bob McLeod in the Northwest Territories (central Arctic), saying he looks forward to working with McLeod “together to create jobs and prosperity.”

Resisting Ottawa’s energy policy

McLeod is the unofficial dean of Canada’s first ministers, earning the title of Canada’s longest-serving current premier after Saskatchewan’s conservative powerhouse Brad Wall left in 2018. McLeod marks eight years as premier of the consensus government of the Northwest Territories in the fall.

In an interview Tuesday McLeod evaded questions about whether he’s part of the resistance, but the two-term premier says he shares their concerns.

“I think there are a lot of things that I have been saying that have been pretty similar with premier-elect Kenney,” McLeod told CBC Politics. “I think that we can accomplish a lot.”

“We are very concerned about the fact that we ask our children to go to school, and we got to keep our end of the bargain and make sure we have jobs and opportunities for them.”

McLeod said, like Alberta, his territory’s oil and gas are stranded and the federal government hasn’t done enough to boost the North’s roads and pipeline infrastructure.

If anything, McLeod said, Ottawa has kept the resources in the ground after the Trudeau government announced a five-year moratorium on oil and gas drilling in Canada’s Arctic waters.

McLeod has denounced the Liberals for imposing the ban without consultation.

Ottawa is working with McLeod on a management strategy for oil and gas exploration in the Arctic that could see the federal government lift the ban.

McLeod said Alberta’s incoming government, facing a struggle to get oilsands bitumen to overseas markets through the approval of the Trans Mountain pipeline, is an ally, but so are other provinces and territories.

“I think working with Jason will help us in that regard,” McLeod said. “And of course we need to work with all the players, including the federal government.”

When it comes to the carbon tax, McLeod said he has his concerns, but the N.W.T. has come up with a “made in the North” climate change plan that Ottawa has approved.

Meanwhile in the Eastern Arctic, Nunavut echoes similar concerns about Ottawa’s energy policy in the North and condemns the federal carbon tax.

Nunavut doesn’t have a plan, and Ottawa will impose its backstop in July as it has on other conservative-led provinces.

Several provinces — including Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario and, Kenney promises, soon Alberta — are challenging in the courts the federal government’s imposition of a price on carbon.

‘No one in Nunavut asked for the carbon tax’

Nunavut’s Premier Joe Savikataaq said his government won’t join the legal fight, but he supports Kenney and other Conservative premiers in their judicial challenge.

“I hope if they win, we would be benefiting,” Savikataaq said. “No one in Nunavut asked for the carbon tax and no one in Nunavut agreed to it.”

Like McLeod, Savikataaq wouldn’t say he’s part of the resistance.

Jessica Shadian, who studies the Arctic, isn’t surprised territorial premiers are working with their Conservative counterparts, given their simmering frustrations in unlocking their energy resources.

“So there is a growing frustration, I would say, in the North, in the sense of not being able to control their own territories,” said Shadian, president of Arctic 360, a non-partisan think-tank that educates financial institutions about opportunities in the North.

But Shadian said she wouldn’t read too much into suspicions territorial and conservative premiers are aligning.

The territories, whose concerns are many, are seeking partners who can help solve them regardless of political parties, she said.

Yukon Premier Sandy Silver was not available for an interview, but said in a release he’s eager to work with Kenney on “creating jobs, protecting our environment and advancing reconciliation.”

The territory’s Liberal member of Parliament also said he’ll work with Alberta’s new government, but Larry Bagnell said reducing greenhouse gas emissions is a huge issue all provinces and territories need to work on together.

In addition to scrapping the carbon tax, Kenney campaigned on lifting the cap on oilsands greenhouse gas emissions, a key element in meeting Canada’s climate change targets.

“Climate change is silently affecting the North,” Bagnell said. “If there are some provinces that don’t do their part to help Canada get to those targets, it will put more pressure on the rest of Canada.”

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: N.W.T. premier Bob McLeod frustrated by slow oil and gas development, CBC News

Finland: The world could transition entirely to cheap, safe renewable energy before 2050: Finnish study, Yle News

Norway: Greenpeace activists board oil platform in Arctic Norway, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Gazprom launches construction of giant gas field in Arctic Russia, The Independent Barents Observer

United States: U.S. Interior Dept. delays offshore drilling plan: report, Alaska Public Media